A recent bid by the Wake County Commission to take over school site ownership and construction isn’t new. In fact, the Commission has been trying to change the way schools are built since at least 2002.

But for the first time in a decade, it appears that the state legislature has the right political makeup to turn the idea into law.

To the majority of Commissioners in Wake County, it just makes fiscal sense.

The Wake County Commission has the power to levy taxes. So why can’t they spend that money on school construction, leaving the Board of Education free to take care of administrative issues?

To the majority of Wake County School Board members, it doesn’t make any sense at all.

The checks and balances of having one body raise taxes and the other spend works, and works well, they say. So why can’t the board continue building schools for the almost 150,000 students in the district?

And as both sides argue their case, they must also work together to get a school bond on the ballot in time for the fall elections.

Commissioners Want Accountability

Commissioners included the proposed the change in their most recent legislative agenda.

State Senator Neal Hunt (R) of Raleigh introduced the bill promoting the county ownership of school sites on March 7. He did not return repeated emails or phone calls for comment.

Currently, the Commission has taxing authority and works with the school board to write bond referenda that are sent to voters for approval. When a new site needs to be built, or an existing building needs repairs, the board asks the Commissioners for money to fund the project.

Wake County Commissioner Tony Gurley said this system is not financially efficient. And, he said, the idea of transferring ownership of school sites and construction from the school board to the county has been floating around for as long as he’s been a Commissioner — since 2002.

Karen Tam

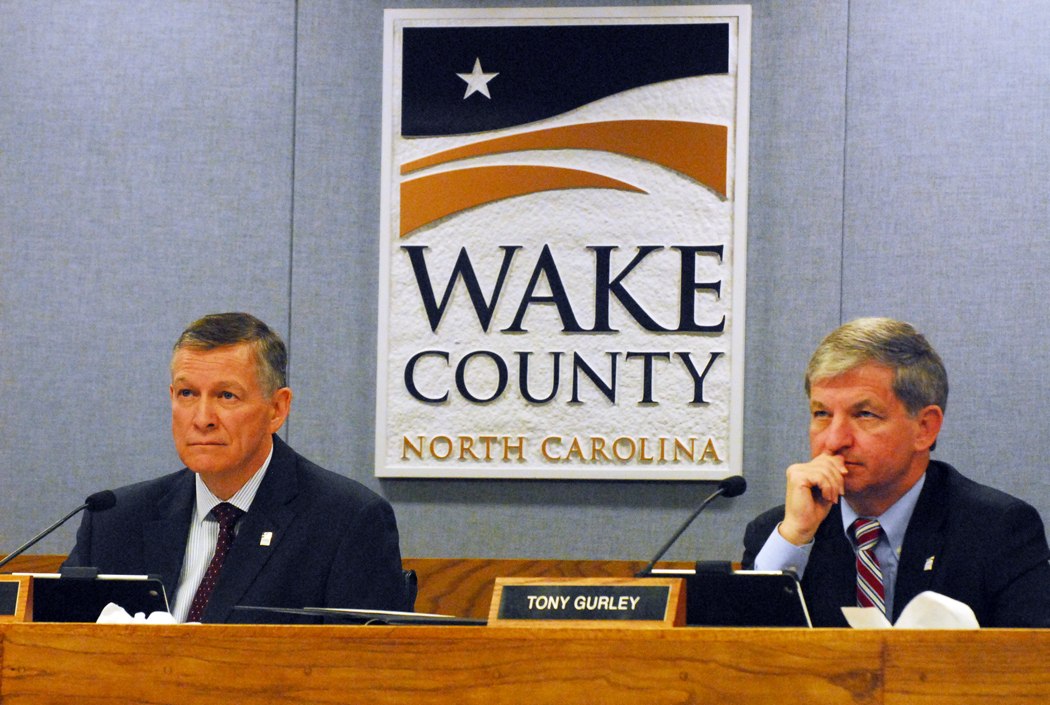

Joe Bryan and Tony Gurley. Photo by Karen Tam.

“I was chairman of the Board of Commissioners when we passed the 2006 school bond,” Gurley said. “I have seen many instances where the County Commissioners are much more fiscally responsible and better stewards of the taxpayers’ money than the school board.”

Gurley said one example of such irresponsibility is the Board of Education’s unwillingness to specify exactly where funds go after they have been successfully requested from the county.

“That shows you that there’s something going on with their budget,” he said. “They’re reserving the ability to divert the money from maintenance into some other part of their budget. Once they get the money, they no longer have to account for it. They’re allowed to divert it into other areas and not seek anyone’s approval.”

Gurley said because the Commission introduces bonds to be voted on, it is more directly accountable to the public.

Commissioner Joe Bryan also likes the idea. He said transferring the duties of school construction away from the board will shake up what has become a stagnated system.

He pointed to the acquisition of the land for the future West Apex High School as an area where the Commission could have possibly gotten a better deal for the site than the school board did.

“What is the best way to protect the taxpayers?” Bryan said. “To give the county an option to change the way things are done. And so the Board of Education isn’t always the Board of Construction.”

School Board: System Not Broken

Commissioner arguments aren’t holding water with board members and their supporters.

Karen Tam

Christine Kushner

School construction is a major part of the education process, with school design and placement akin to a teacher setting up a classroom to his specifications before the year starts, said Christine Kushner, vice-chair of the Board of Education.

“I see this as a solution looking for a problem,” Kushner said. “There’s no problem, so there’s no need in my mind to alter the way schools are being built in Wake County.”

Chair Keith Sutton agreed.

Karen Tam

Keith Sutton

“We have a proven track record, and a successful track record of maintaining ownership of the school buildings,” Sutton said. “We have won a number of awards for our facility design, construction and energy savings.”

Learn More: How sites are selected by WCPSS

Sutton also expressed concern about the minutiae of school upkeep. If a window is broken, he said, they would get it fixed as soon as possible, rather than asking the Commission every time.

“That process could become pretty lengthy or timely, if meeting once a month or twice a month and you have to wait until the next meeting to get approval to replace a fixture, add a door, add modulars, or what have you,” Sutton said.

In response, Bryan said that he would like to see the day-to-day upkeep of the schools remain as it is now, with the Board of Education handling routine maintenance requests, or managed by the Commissioners like any other county building.

Special Situation

About 90 percent of school boards in the U.S. do not rely upon another local government for their local funds, according to Leanne Winner, director of governmental relations for the North Carolina School Boards Association.

She said there are two important reasons to keep school construction in the hands of the school board: student assignment, including where and what kind of schools to build, and the programmatic side, which determines what type of school and what kind of programs you can offer at that school.

“School construction is an extremely specialized area,” Winner said. “We have requirements based upon the federal IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) requirements. If you’re going to have students there that might have audiology issues, there might have to be specifications for wiring, things like that. There’s a whole host of issues and those are extremely different than ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) issues.”

She also said schools with, pre-K classrooms have to be designed differently, due to the younger age of the children and, in light of the Newtown school shooting and other public tragedies, school safety.

One argument that has floated around for the last decade or more is that the move will make the county’s finances look balanced.

“The County Commissioners say that it would help them to align the assets with the liabilities, but that point has not proven to be a true or accurate one,” Sutton said.

According to governmental accounting regulations, governments must report all assets and liabilities on the same page. But since the Commissioners must grant the money to another body, they accept the liability. The new assets — constructed or updated school facilities — are counted on the school board’s records, not the county’s. This gives the appearance that the county is in a deficit.

“We spent a great deal of time at that juncture with the local government commission and the treasurer’s office talking to the three bonding agencies in New York,” Winner said. “They assured us that they understood that North Carolina was in a unique situation where the asset was on the school system’s books and the debt was on the county’s books and that they would realize that when they were looking at the bonding documents, and it would not affect our bond ratings.”

The county has maintained a pristine AAA rating for decades, Gurley said, so while it would be nice to have balanced-looking books, it is not one of the main reasons the issue of ownership has come up time and again.

“An accounting function is not the reason we’re doing this,” he said. “We’re doing this because we will be more responsible with the taxpayers money, and it’s good policy.”

Going Forward in 2013

In the midst of this tumult, the two bodies are working together to try and produce a school bond referendum for the fall 2013 election.

“I’ve been very concerned that it does color our discussions of a very needed capital bond, because the county does have a responsibility to build and maintain schools,” Kushner said.

She also said the county’s responsibility for funding and passing bonds is the cheapest and most effective way to raise money for the schools. Sutton agreed, and said having the bodies do discrete jobs but work toward a common goal is a benefit.

“In my opinion, that’s an intentional separation of power that was put in place by the General Assembly,” Sutton said.

But to the majority of Commissioners, the old system can’t keep up with the needs of a growing county. And for Commissioners like Gurley and Bryan, who have served the county for many years, the uproar over the proposal is confusing.

“We’ve been bringing this up for the last six years or more, with support from the Wake Ed Partnership and the (Raleigh) Chamber of Commerce,” Gurley said. “This has been an ongoing process, and they’re all so new, they don’t know the history. For them to claim this is a surprise is naive.”

Despite the history behind the proposal, both groups agree there was a lack of dialogue about the transfer before it was introduced as an agenda item.

“The leadership of chair and vice chair of the board of commissioners and chair and vice chair of the school board routinely get together, and that was never raised as an issue, so that was disappointing to see that on their legislative agenda,” Kushner said.

Bryan said he would have liked a transition to take place first through negotiation, but that the current law stipulates how boards of education and counties interact with regard to school buildings.

“Presumably, if the bill passes, I’d like to see a friendly, negotiated merger,” he said. “What we will get is a true partnership,” he said. “What we have now, it’s not really a true partnership.”