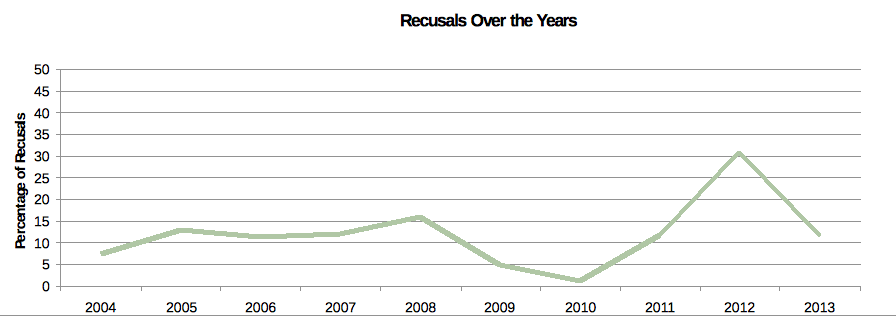

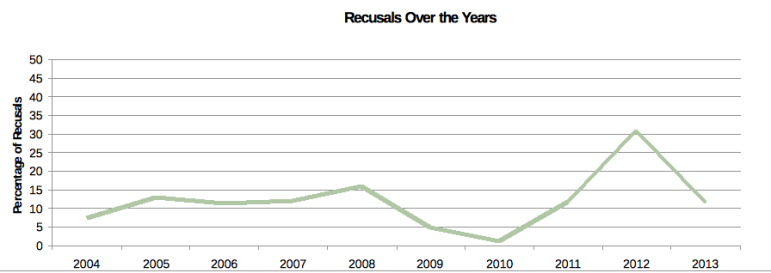

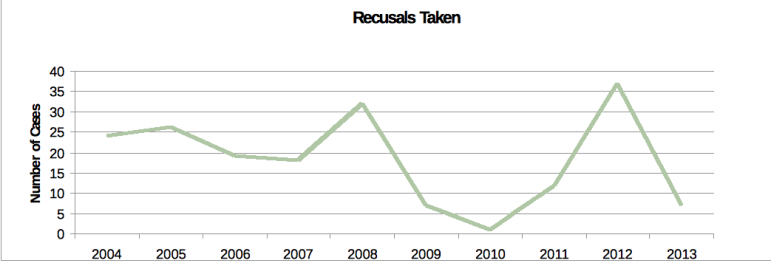

Volunteer members of the city’s Planning Commission recused themselves from nearly 30 percent of the cases brought before them in 2012, a significant increase over a previous five-year average of 10 percent, a case-by-case analysis of Commission minutes by the Raleigh Public Record shows.

The first six months of 2013 have seen the percentage of recusals fall back to previous-year levels, and the implementation of the new Unified Development Ordinance plan in September will likely cause it to drop even further as the Commission moves away from hearing site-specific zoning and land use cases and focuses more on long-range planning and development for the city.

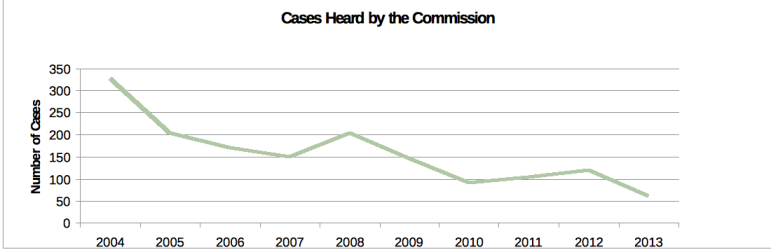

Planning Commission members, who reviewed about 120 zoning and site plan cases last year, are required by state law and city guidelines to recuse themselves for a variety of reasons – a familial, business or personal interest in a case, for example – and in practice they tend to err on the side of caution.

Exceeding the Guidelines

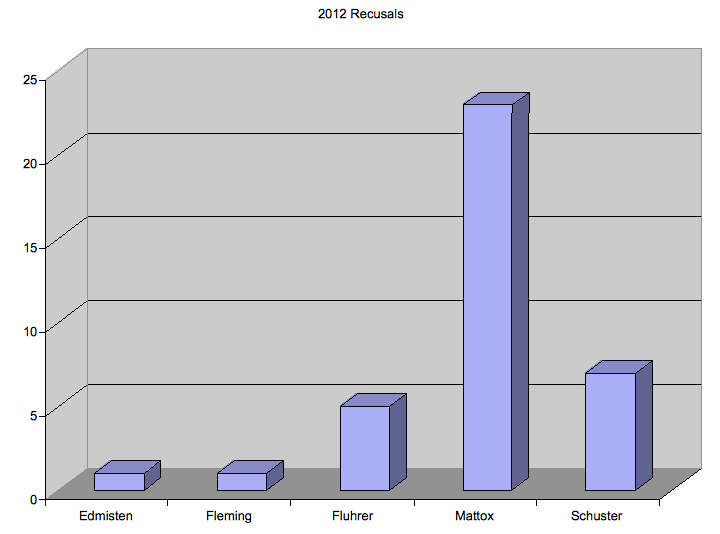

Isabel Mattox, a land-use attorney who joined the Commission in 2010 and now serves as its chair, was responsible for 62 percent of the 2012 recusals. Mattox explained that she recuses herself not only from cases she may have worked on personally, but ones on which close colleagues may have worked on as well.

“I think it’s useful to have people on board, the Commission that have some experience, some expertise or knowledge in certain areas,” Mattox said. “Therefore, if you have people working in that area, generally, they’re going to have some cases where they’re going to recuse themselves.”

Steve Schuster, an architect with Clearscapes who also sits on the Commission and whose recusals accounted for 20 percent of the overall 2012 numbers, agreed with Mattox’ assertion.

“Obviously we all subscribe to and are committed to following the city’s policies on conflict of interest,” Schuster said. “So I think you’ll find for many of the commission members, they recuse themselves often beyond what the city’s policy would mandate.”

Schuster said for example that even though he is heading up Clearscape’s design of the new Union Station, he will recuse himself when the case comes before the Commission and have one of his partners make the presentation.

“It would appear to me, if I’m on the Commission and making the presentation, that it will carry more weight than it should,” he said. “This will remove me even a step further away from having any influence over what the Planning Commission might do.”

He added that members actively seek to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest.

“If there’s even a potential, I tend to recuse myself, I don’t want there to be a possibility of someone saying, ‘That’s inappropriate,’” Schuster said.

Ken Bowers, the city’s deputy planning commissioner, explained that a slight uptick in recusals means simply that the commission is doing its job.

Members, he said, “have to weight their business interests against their service on the commission.”

“It can have an impact on their business because they can’t represent their clients – my guess is it probably has a negative impact,” Bowers said.

Serving the Community

Nine of the 10 members of the Planning Commission are appointed by City Council, with one appointed by the Wake County Commission. They serve for periods of two years and can not serve more than three consecutive terms. While they make recommendations on issues pertaining to zoning issues and site plans, it is ultimately up to the City Council to grant final approval.

Eric Braun was a partner at the law firm K&L Gates and taught municipal law before joining the Commission earlier this year. Although he was diagnosed in 2001 with multiple sclerosis, Braun continued to work through 2010, when his doctor told him he needed to quit working and focus on his health.

“I’d been doing some community volunteering when an opportunity opened up on the commission,” Braun said. “I used to represent local governments, I’ve represented developers, I kind of have a broad range of experience.”

“I’m not ever going be able to work again, so I don’t have any allegiances to anyone,” he added, explaining why his role on the Commission is somewhat unique.

Although cases have come before the Commission on which he had past involvement, Braun has yet to recuse himself and said some members have a tendency to do so in situations where they are not legally required to.

“The law technically requires people to recuse themselves in a pretty narrow set of circumstances, but there’s nothing wrong with being more cautious,” he said.

“I think there’s more pressure to be more … conservative out there now, because there’s so much information available, someone could look back and say ‘You represented these people, you should have recused yourself,’” Braun said, echoing the sentiments expressed by Mattox and Schuster.

The only time recusals could become a problem, Braun added, was if there were so many that it reduced decorum and the body was unable to conduct business. In the 10 years of minutes reviewed by the Record, there were only 10 instances in which more than one Commissioner was recused from a particular case. Even in those instances, there were still enough members to vote and make recommendations on the cases.

The meetings, held at 9 a.m. on the second and fourth Tuesday of each month, often run long. Braun said member absences – around 180 in 10 years — and early dismissals — averaging around six per year since September 2003 — are more likely to impact decorum. He could not recall an instance where a case had been pushed back due to a lack of available members. Data reviewed by the Record supports this.

A New Role for the Commission

Starting Sept. 1, all new site and zoning plans will go through a new process where their cases are heard by the Board of Adjustment, as determined by the Unified Development Ordinance plan.

“We’re returning the Planning Commission more to its roots,” the planning department’s Bowers said.

“The city charter language talks about the commission taking a long-range view of the city and developing plans and ordinances to implement that long-range plan.

“Our commission has been so consumed with the twin duties of recommending zoning and having approval over certain site plans that [long-range planning] tended to get lost in the shuffle,” he said.

Bowers explained that in a rapidly growing city such as Raleigh, it was important to create strong and clear standards in the code, so that applicants – developers, architects, residents – would have a clearer picture of the rules, regulations and requirements necessary to move forward.

The new policies would also largely remove City Council from having to make decisions on individual cases – which Braun sees as a positive step in the right direction.

“I think having the Council make decisions on specific projects; they’re supposed to be made on a technical basis, do they meet the code or not, it’s not supposed to be a subjective decision,” Braun said.

He added that political pressures, particularly in the lead-up to an election, can make it difficult for an elected body to make objective decisions on zoning and land-use issues that may directly affect their constituents.

“If you have every specific project going before City Council, they get bogged down in the details. Instead they should be looking at bigger-picture projects like transit or bond issues or big ticket items,” he said, “Not whether there’s going to be another convenience store on some corner.”

Bowers said the changes implemented by the Unified Development Ordinance were not in any way a reflection on the work being done by the City Council or the Planning Commission, but rather were a way of streamlining the development process and making it easier for outsiders unfamiliar with the local political landscape to come in and make their voices heard.

“I think, in general, our planning commission has done an excellent job,” he said.