Brought to you by Rufty-Peedin Design Build

Wednesday, July 27, 2016

(press play)

Ten years is a long time. People, places, things; they change over the span of a decade.

Take Raleigh, circa 2006. It wasn’t a “Top 10” city. The population was a mere 363,267. Charles Meeker was still Mayor. Downtown Raleigh was a ghost town after 5 p.m. And as you saw in the video above, Fayetteville Street was a pedestrian mall, cut short on the south end by a vast, concrete ’70s-era civic center.

Of course, 2006 was also the year much of that began to change. On February 19, demolition began on the old Civic Center, and on July 29, Fayetteville Street was reopened to vehicular traffic.

Nearly 100,000 people have moved to the City since then, and for at least one of us, seeing that old Civic Center — which from the right aerial angle resembles a four-top circus tent — right dead in the middle of Fayetteville on top of City Plaza came as quite a shock. What *was* that bulky, alien structure? Where did it come from?

City of Raleigh

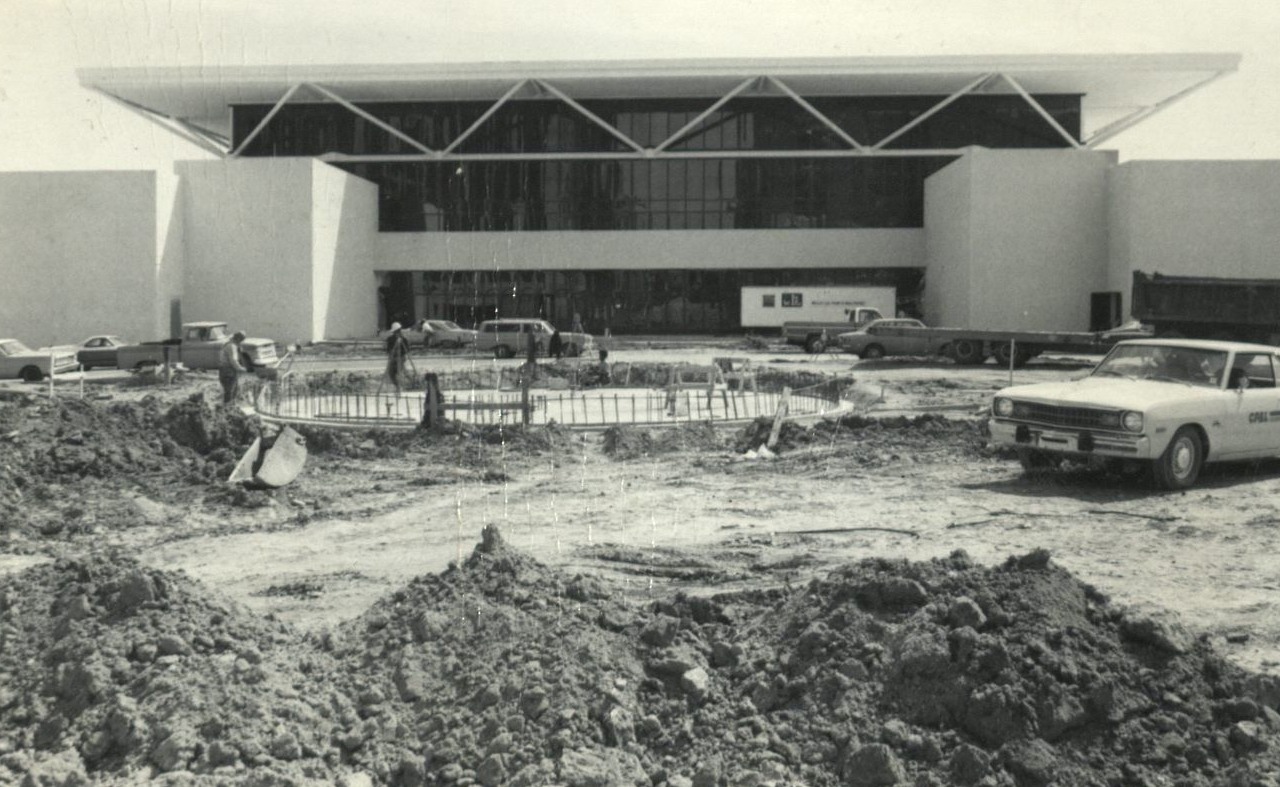

The old Raleigh Civic Center

The Raleigh Civic Center officially opened its doors on September 15, 1977. According to a contemporary report from the News & Observer,

As 1,100 people filtered into the Raleigh Civic Center for Thursday’s official opening ceremony, the recorded voice of pop singer Petula Clark floated down from the sound system in the ceiling 50 feet overhead.

“Downtown,” she belted out, “everything’s waiting for you.”

City officials promised the Center would be a great source of civic and economic prosperity. Former Mayor Thomas Bradshaw said at the time that “The event we are participating in today will insure this community’s health and vitality for many generations to come.”

While the Center did manage to turn a profit throughout its 29-year life span, there was one slight problem: most people considered the place an eyesore.

A Bunker on Fayetteville Street

“No one liked it; it was a $6 million dollar building,” said Roger Krupa, director of the Civic and then Convention Center from 1980 through 2015.

“The City was really pretty judicious in how they spent their money,” Krupa told The Record earlier this week.

“What [architect for the Civic Center A.G.] Odell did really made people mad,” Krupa said.

“He also designed the Archdale Building, and what he did is he took the two terminals of the City, the Capitol Building and Memorial Auditorium, and he built the Civic Center in front of the auditorium, and he built the Archdale Building on the other side of the Capitol.”

The Archdale Building

“He built his own two terminals; it was bad.”

Not surprisingly, Odell was from Charlotte, where he had previously designed the Queen City’s Civic Center. We were unable to verify whether Odell’s new terminals were the spark that ignited the eternal flame of the Raleigh v. Charlotte wars, but we’re sure of this: they didn’t help things any.

Although several contemporary news reports made reference to Raleigh’s “$18 million” Civic Center, Krupa said this figure is a bit misleading.

Half of that $18 million in bond money was spent on land acquisition, he said. That $9 million bought the City the land that now holds City Plaza, the BB&T Tower, the Sheraton and the underground parking garage.

$6 million was spent on the building itself, and the remaining $3 million went toward interiors and fixtures. It’s probably worth noting here that the headline seen in the video where 175 men were reported as “swallowed up” by the Center was simply a reference to the large job site required by this $6 million project.

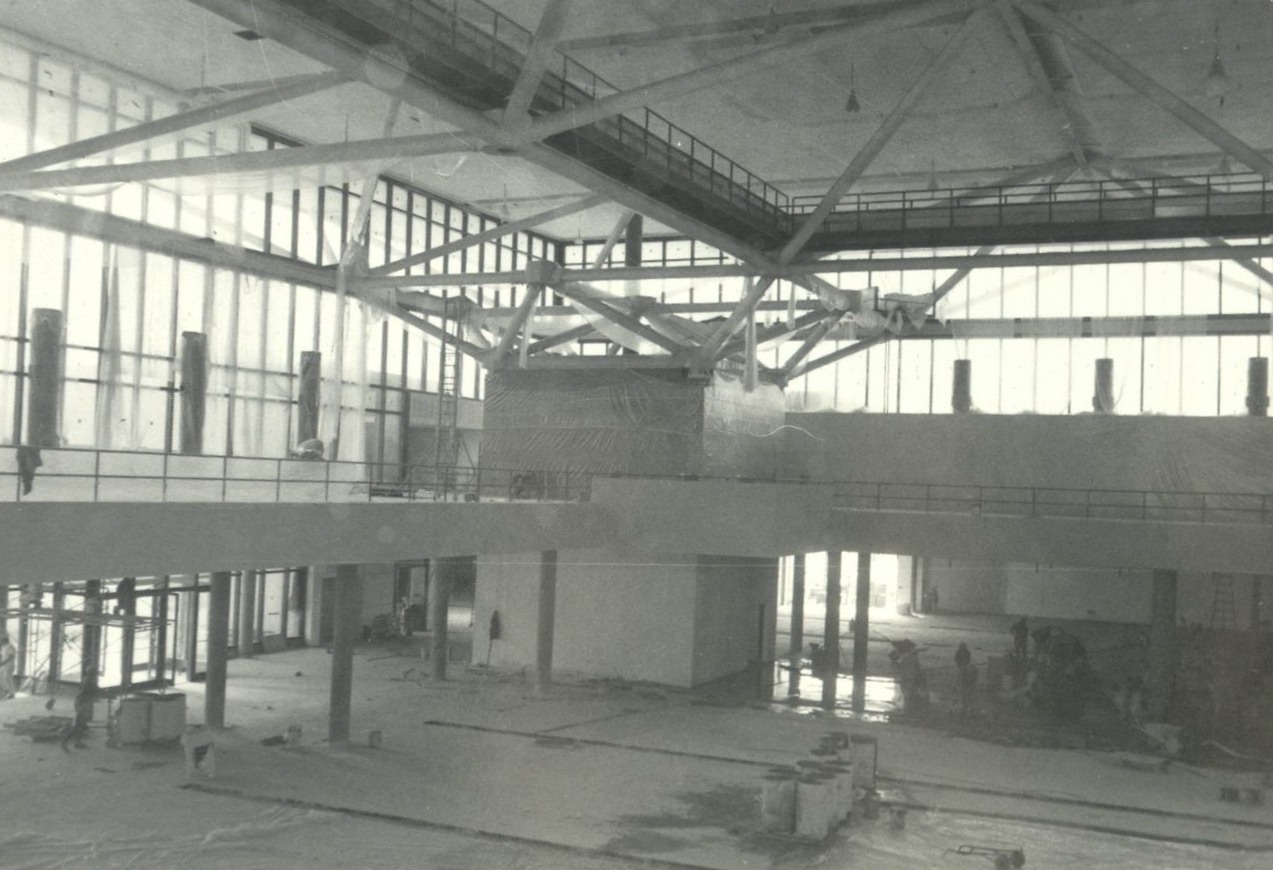

One of the key problems with the building’s design, Krupa said, was that Odell had tried to create “a space-frame structure that you could see through.”

[ed. note: Per Wikipedia, “a space frame or space structure is a truss-like, lightweight rigid structure constructed from interlocking struts in a geometric pattern. Space frames can be used to span large areas with few interior supports.”]

“That space frame was on the outside of the building, so on the inside of the building it’s basically glass on the North & South sides; the original rendering showed you looking through that space,” Krupa explained.

“What happened was, when they got into the heat loads, they understood the glass could no longer be clear, it had to be tinted, it became dark glass and you couldn’t see through it.”

“He forgot about heat loads.”

City of Raleigh

The old Civic Center seen from the Fayetteville Mall

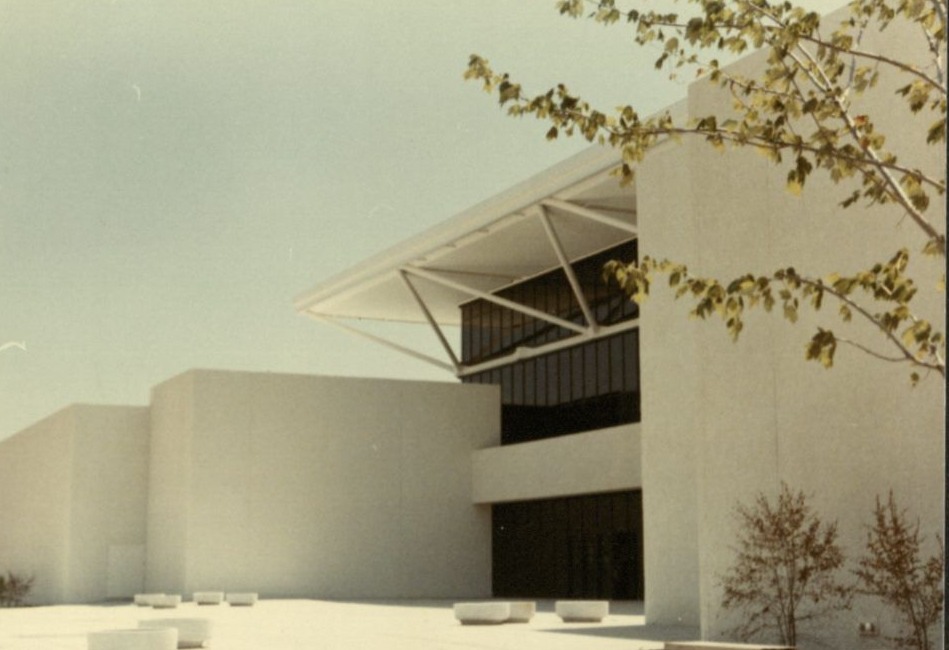

The darkened glass, combined with the poured-in-place concrete that made up the rest of the Center’s exterior, lent the building a “bunkerlike” appearance, said local architect Steven Schuster.

Schuster, whose firm Clearscapes worked on Raleigh’s new Convention Center, which opened in 2008, said while it’s easy to critique the design of the old Civic Center, it’s also “difficult to criticize with 21st-century eyes design decisions made in the mid-20th century.”

“It was fairly opaque building; it really did not engage street in any meaningful way,” Schuster said.

“It was also designed at the time when there was a perception that downtowns were not that safe, and therefore, if you’ve seen photos of the building, except for the glass on the North and South faces, all the walls were poured-in-place concrete: it was somewhat bunkerlike in its appearance.”

The interior wasn’t much better.

“There were some meeting rooms, but not that many: the main space was one of those one-size-fits-all,” Schuster said.

“I mean it actually had some basketball games; there were boat shows, concerts: all kinds of things. It was too ambitious to have one space do everything, so it generally did everything not that well.”

A Successful Run & A Tearless Goodbye

While Krupa would certainly agree with Schuster’s aesthetic assessment of the building, he considers the old Civic Center, with its one-size-fits-all main space, a notable success.

“I think it was a very successful public facility: we actually made money in that building, a lot of people forget that about that building: it made money,” Krupa said.

“We had 400 events a year, mostly public: home shows, car shows, boat shows, women’s shows, Christmas Shows.”

Krupa said when the 400-room Radisson, now Sheraton, was built downtown, another 300-room hotel in Mission Valley just outside of downtown was torn down.

“There was never a scale of rooms to work for conventions; add in the fact that the Radisson did OK with transient business and didn’t really want conventions during the week, it wanted them on weekends,” he said.

“But we made all our money on weekends with car shows, etc. so we kind of parted ways amicably [with the hotel.]”

“The priority in the new Convention Center is room nights; the first thing you have to produce is room nights: in the old building, we didn’t care about room nights at all.”

“It served its purpose for its time; it wasn’t nearly the dynamic downtown we have today: it was a stopgap measure.”

City of Raleigh

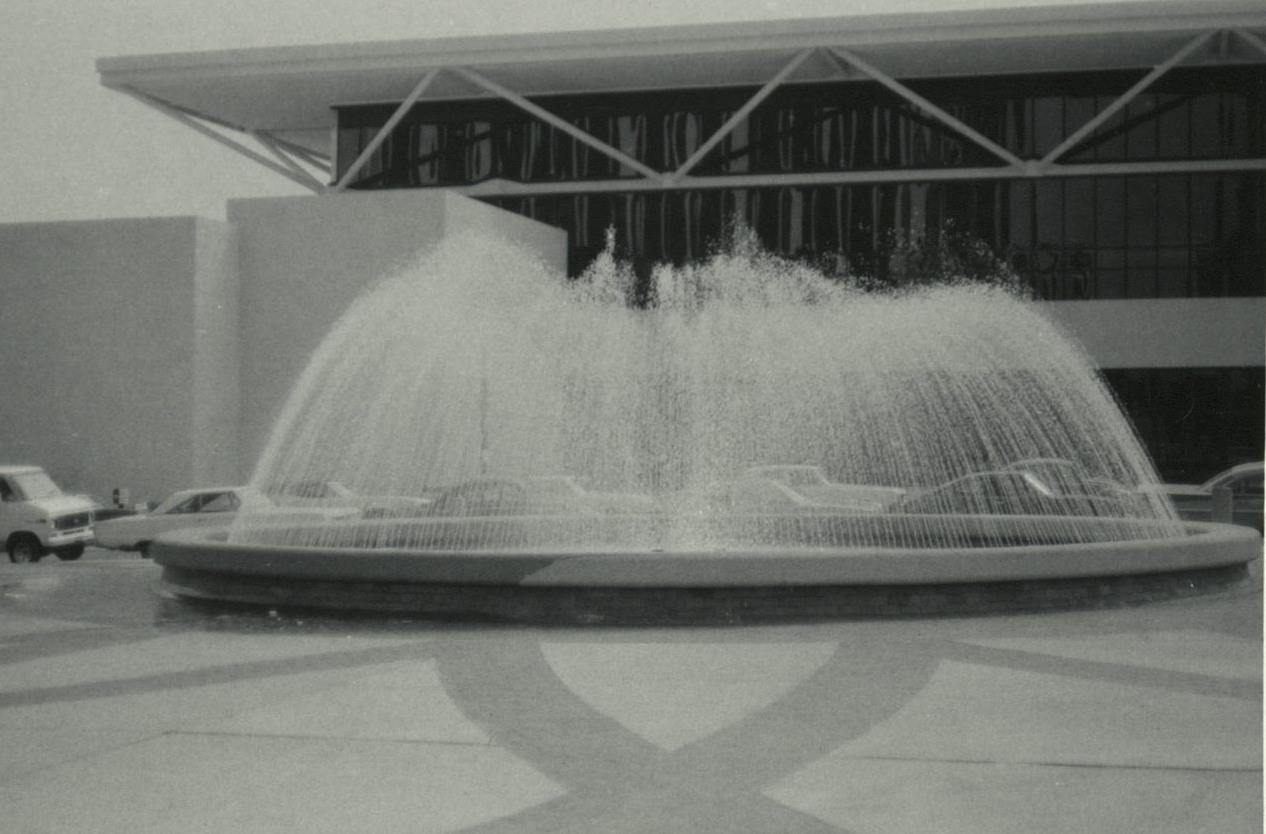

The Civic Center in happier times

When the original Civic Center was built, Schuster said, the City was operating on a very different set of priorities than it is today.

“That was a time when there was very little interest or demand for retail space in downtown, and the thinking was, believe it or not, was that Fayetteville Street was too long, and if we shortened it, it would be a more vibrant Main Street,” Schuster said.

“So by plopping the Civic Center in the center of the street and thereby shortening it, the goal was that what was left would be more vibrant. Shortly after that, the Fayetteville Street Mall was put in place.”

“These were noble ideas that turned out to be not that successful,” Schuster said.

“There were a lot of downtowns starting in the late 60s through the 80s,” he said, “Where there were a lot of noble attempts of, what can we do to revitalize downtown: a lot of communities tried malls [similar to Fayetteville St.]; with a very small number of exceptions, they failed all over the country.”

By 2006, the City’s priorities had changed significantly. Downtown was again in need of revitalizing, and instead of closing off “Raleigh’s Main Street” they planned to open it up, tear down the old Civic Center and build a brand-new Convention Center.

By all measures, the City’s efforts over the last decade have been a tremendous success, as Raleigh has continued to grow and develop at an astonishing rate, earning countless accolades along the way. The new Convention Center, Krupa said, has exceeded all expectations.

Of course, before any of that could happen, the old Civic Center had to go.

Stacy Loizeaux, a third-generation member of the family behind Controlled Demolition Inc., which was contracted to do the implosion work, remembers witnessing the Civic Center’s roof come down all those years ago.

“It wasn’t a big job; the building was a bit of an eyesore, I think people were glad to see it go,” she said.

Due to the small size of the job, Loizeaux said they had hardly any records on it; they drilled 300 holes, she said, and the building was listed at 73,728 square feet. The implosion happened at 7:05 a.m. on February 19, 2006.

Permits valued at $3.2 million for the job were issued to general contractor Holder Construction in October of 2005. Those permits listed the size of the structure at 130,000 square feet.

As described in a great article from Indy Weekly at the time, the implosion was only designed to lower the roof. Another firm, P&J Contracting out of Baltimore, went on to tear down the entire structure.

Krupa, who observed the implosion firsthand, also remembers the day well.

“There weren’t a lot of tears.”