This story is the first of a two-part series examining how the City of Raleigh works to control pollution in its drinking water watersheds. Next week, part two will examine land conservation practices.

Raleigh City Councilors Tuesday authorized the city attorney’s office to challenge the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources renewal of a permit on the grounds that it is a violation of the Falls Lake Rules and federal environmental policy. The city challenged the same permit last year for the same reasons.

The general permit, valid for five years, does not address what Raleigh sees as a source of nutrient pollution to the city’s water supply: new construction allowed to use discharging sand filter septic systems and existing systems that are not inspected before permit renewal.

John Hennessy, supervisor with the state Division of Water Resources, said sand filter systems are usually only used when “the landowner has no other options than these permits. It is really a permit of last resort. If you can’t hook up to municipal sewer, it is your last resort.”

As many as two-thirds of the permitted systems have city sewer available now, though that may not have been the case when the systems were installed. The Falls Lake inventories, completed in January of this year, show that there are at least 1,161 sand filter systems in the Falls Lake watershed. At least 716 of those have city sewer available.

DENR regional representatives inspect plans for new systems authorized under the permit to ensure that the site is suitable for the proposed system. But when a permit holder renews every five years, they only need to submit a notice of intent and payment to the state. DENR does not verify whether those systems are still operating properly.

Dan McLawhorn, with the City of Raleigh, said “any new development must use nitrogen and phosphorus reducing techniques that reduce substantially loading to a background level so that it is not possible to add new nutrients.”

Nutrients in this case mean pollution from septic systems.

The Falls Lake Rules required local governments to draft policies for new construction.

Those went into effect in July of 2012—essentially stopping the addition of new human-caused nutrient sources in the watershed.

McLawhorn said that while local governments and developers have stopped adding nutrient pollution to the watershed, the state is “reserving this one piece for themselves. They maintain the authority to close the loophole, and they refuse to close it.”

He said that Raleigh’s interest is in ensuring that developers and homeowners either use a septic system that is more environmentally friendly or buy credits to make up for the pollution they are adding to the watershed. The new permit requires neither, he said.

During the public comment period on the rules this spring, Steven Berkowitz, on-site wastewater engineer with the State Health Department, pointed out in his written comments the contradiction between the nutrient reductions required by the Falls Lake Rules and the lack of reduction required by the permit.

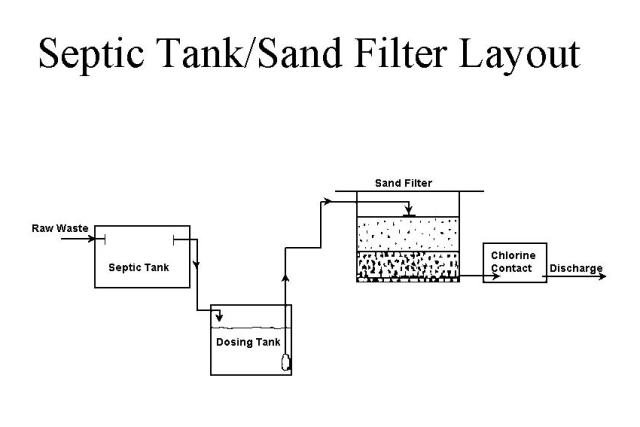

Raleigh’s primary complaint is about discharging sand-filter systems. In these systems, household wastewater from toilets, dishwashers, sinks, and bathtubs flow to a septic tank.

From the tank, the water flows to a sand drain field and then to a pipe that discharges to a stream, ditch, or other low spot.

The City of Durham estimates the cost per connection to city sewer at $12,015 per connection for its 191 systems with city sewer available — $2.3 million total.

Hennessy said the contribution from sand filter discharge systems is infinitesimal. Durham’s nutrient-source inventory shows that connecting 191 sand filter systems to city sewer would prevent 220 pounds per year of nitrogen and 67 to 68 pounds per year of phosphorus from entering the lake. Including the Durham County sand filter systems could nearly triple that amount.

To put that in context, if the owners of these systems were required to buy nutrient credits at DENR’s rate, the annual total would be $4,763 for nitrogen and $14,068 for the phosphorus. In addition, the Falls Lake rules require new home sites to discharge no more than 2.2 pounds of nitrogen and .33 pounds of phosphorus to the lake per acre per year.

The EPA forced the state of Illinois to stop permitting discharging sand filter septic systems because of the resulting nutrient pollution. McLawhorn said, “It was so dissatisfied with Illinois allowing these things to proliferate with no real controls.”

Litigation is not a foregone conclusion.

“If the division [of water resources] becomes active in talking with us we may postpone litigation and move forward to try to reach consensus,” McLawhorn said.

Part two of this series about nutrient pollution will appear next week. In that story, we will look at state changes to land conservation policy and how it affects the city and local nonprofits.