Raleigh City Councilors are getting serious about reversing a citywide recycling rate that’s 70 percent lower than the national average.

Recycling, they say, is one of few services that can both save and make the city money. More recycling means fewer costly tons of trash dumped in Wake County’s South Wake Landfill each year, and more plastics, paper, aluminum, glass and cardboard to sell for a profit.

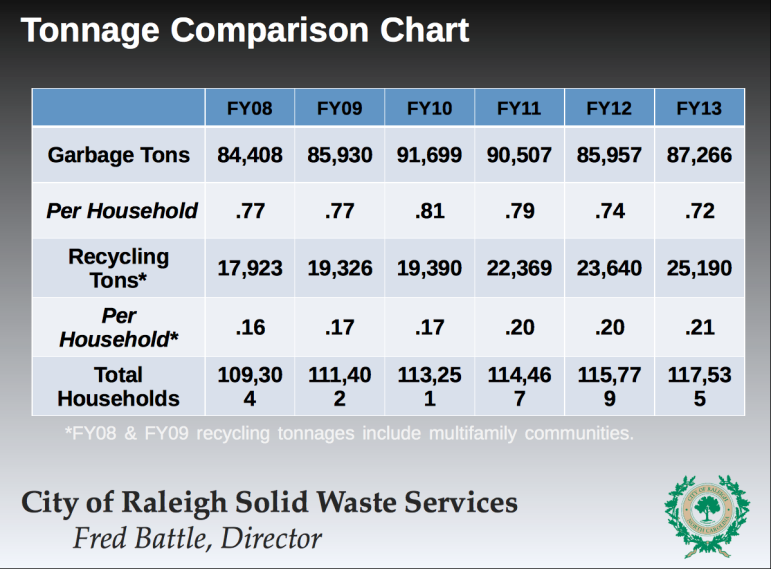

Recycled tonnage has already grown from 17,923 in 2008 to 25,190 this year, helped by the replacement of 18-gallon green bins with more than 115,000 95-gallon blue carts since 2010, but Council members want to know what else they can do to get more residents and businesses recycling.

Karen Tam / Raleigh Public Record

Raleigh’s rate of household waste diverted from the landfill is about the same as Charlotte and Wilmington, but below that of Asheville, Cary and Greensboro. And according to the International City/County Management Association, its recycling rate per account (including multi-family communities) was 0.14 of a ton in 2012, compared to the national average of 0.24.

“We have a desire to do better, to really see if we can increase our recycling and decrease the trash we’re putting in the landfill,” said Mayor Nancy McFarlane. “Our goal is for the big blue carts to be full and the trash cans to be very empty. So which program will give us that result?”

Several options are on the table after a Nov. 12 meeting of the Budget and Economic Development Committee. Solid Waste Director Fred Battle has six months to report back on the costs and expected return on investment of the following initiatives:

- An incentive program for household recycling, similar to one used in Chesapeake and Norfolk, Va. Called Recycling Perks, the program requires a recycling hauler to scan the radio frequency identification (RFID) tag on each blue cart when its contents are collected. That data would allow the city to reward residents who recycle with points that can be redeemed for discounts and incentives at hundreds of local businesses. In Norfolk, recycling tonnage increased about 10 percent each of the first six months of the program, and recycling participation grew from 45 percent to 60 percent, said Recycling Perks President Bill Dempsey.

- Pay-As-You-Throw is a program cities such as Austin use to incentivize residents to recycle. There, residents are charged for the amount of trash they throw away rather than a flat fee. In cities where trash collection is covered with tax dollars, residents can receive rebates for throwing away less trash.

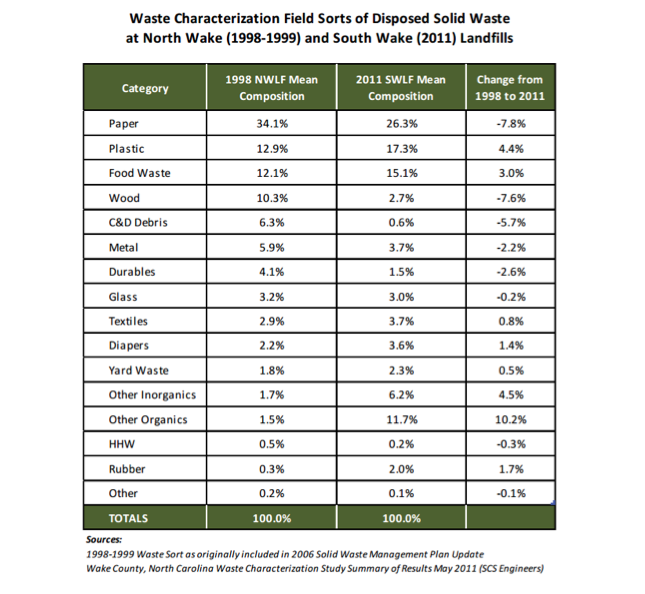

- An organic waste-recycling program for businesses could help divert the 15 percent of Raleigh garbage classified as food or organic material waste. Seattle is a model for this program. It has contracts with hauling companies to collect and compost food waste from hundreds of businesses.

Leo Suarez / Raleigh Public Record

Big Belly trash cans save the city thousands of dollars each year.

- A recycling mandate by city ordinance, which would require residents and businesses to recycle any item possible. San Francisco has used a 2009 mandate to increase its diversion rate from 46 percent to 80 percent since 2000. It now has a goal of having zero waste by 2020.

- Expansion of the multi-family recycling program from 570 communities to include all 756 communities in the city. And more Big Belly solar-powered trash compactor/recycling collectors along city streets, parks and common areas to encourage “on-the-go” recycling.

- Increased marketing and education about recycling. Raleigh spends 45 cents per resident on marketing and the national average, according to the Solid Waste Association, is $1.

Battle’s goal is to come up with a plan that will increase the amount of waste diverted from the landfill from 35 percent (including yard waste) today to 50 percent within five years. That would save a portion of the $33 per ton the city must pay to dump garbage in the landfill.

It would also help extend the life of the landfill. Planned to hold 25 years’ worth of garbage when it opened in 2011, the landfill should already last five to seven years longer thanks to the blue cart program, Battle said. Raleigh will dump 87,266 tons of garbage this year, down from 91,699 in 2010.

Karen Tam / Raleigh Public Record

But the key factor in any new program is how fast it will pay for itself. For example, the blue cart program cost $1 million each of the last four years, but is now saving the city $2 million in annual expenses. The larger cart lets the city collect recycled goods every two weeks instead of weekly. That means fewer trucks and 27 fewer people on staff since 2010.

Battle is most enthusiastic about Recycling Perks, a program he believes would pay for itself within a year and generate $300,000 in new recycling revenue for the city each year after that. That’s based on the current contract with Sunoco, which purchases all of Raleigh’s recycled items at $30 per ton.

Recycling Perks’ Dempsey said his company uses the carts’ existing RFID tags to track and then target areas of town where recycling rates are low, helping to have a lasting impact on waste reduction. In most cases, residents can earn up to $25 per month in rewards for recycling.

“We can look block by block, neighborhood by neighborhood. We’re very strategic and targeted to who we’re communicating with because we want to find the people who need more education,” Dempsey said. “Our goal is to make this a win for everybody. Residents win, the city wins, businesses win because they can advertise for nothing and the world wins because we’re recycling more.”

Mayor McFarlane is eager for the results of Battle’s studies, and to move forward with the next phase of Raleigh’s new emphasis on recycling.

“Anything we can do to decrease costs and save the city money is always a good thing,” she said.