Despite repeated complaints and filings from the Upper Neuse Riverkeeper to the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources, a development in Johnston County continues to pollute Mark’s Creek with sediment.

That particular pollution is likely not the only one not receiving attention: DENR issued its last fine for sediment pollution in April of 2013 — the only fine assessed since the Gov. Pat McCrory-appointed Secretary of DENR John Skvarla started his term.

Matthew Starr / Upper Neuse Riverkeeper

Sediment flows into the woods near the Riverwood development. Sediment is supposed to be contained on site.

The Riverwood development in Johnston County, owned by the Fred Smith Company, has been polluting Mark’s Creek with sediment since May. Caviness and Cates, a company developing some of the Riverwood sites, has also failed inspections.

Neuse Riverkeeper Matthew Starr described it as a “mud river,” flowing off of the property and into Mark’s Creek, a tributary of the Neuse.

Starr said, in spite of filing repeated complaints with DENR since May of 2013 the pollution continues.

Starr said, “I’m not sure if DENR lacks the resources or the will” to enforce the state’s Sediment Pollution Control Act of 1973, the act that regulates mud, dirt, and silt flow from land-disturbing activities. Sediment is still the number one pollutant in NC rivers, as it was when the Act was passed into law.

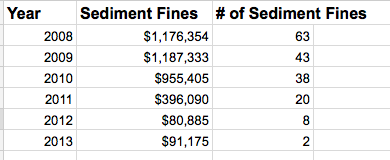

Fine revenue, which helps fund public education, has dropped from $1 million per year prior to 2012 to less than $100,000 per year in 2012 and 2013.

Sediment pollution occurs when land is disturbed, usually by agriculture or construction, and rain washes the exposed dirt downhill into nearby streams. The law requires that all sediment be retained on site.

Sediment reduces the holding capacity of drinking water reservoirs, making them less resilient in times of drought. It can destroy aquatic life and habitat, adding the stream to the state’s list of impaired waters. Sediment can clog and wear out drinking water intake pumps. Its effects cost the tax and rate payers of North Carolina money.

The Riverwood Development

At Riverwood, sediment has reached “the streams and waters of the state,” according to John Holley, regional engineer with the Land Quality Section of DENR. “Those become water quality violations.”

Donnie Adams, president of Adams Engineering and spokesperson for the Fred Smith Company, and David Orringer, the community representative in Clayton for Caviness and Cates, both said that they are doing their best to follow the law. But DENR records show repeated violations.

Matthew Starr / Upper Neuse Riverkeeper

A sediment catch pond near the Riverwood development is full.

Will Hendrick, associate attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, said, “the most egregious violation was that development began before the developers had the required erosion control plan approved.”

A plan is required anytime more than an acre will be disturbed.

The Fred Smith Company received an approved plan in August, months after starting work.

Caviness and Cates was cited in a December inspection report for developing new sites without an approved sedimentation control plan.

The Fred Smith Company is owned by Fred Smith, the former state Senator, gubernatorial candidate against McCrory in the 2007 Republican primary, and 2012 appointee by Governor McCrory to the North Carolina Economic Development Board.

Caviness and Cates builds homes around central and eastern North Carolina and was named a Top 100 Builder by Builder Magazine.

Following an inspection on July 3, 2013, Adams, working on site for the Fred Smith Company, told DENR that a “work order was approved” and sediment would be removed from the area near Mark’s Creek starting on July 5.

A DENR inspection two weeks later found that sediment was still present in that location.

Since then, Starr said, “the situation has only gotten worse. I would go visit and see that nothing had been done.”

Matthew Starr / Upper Neuse Riverkeeper

A silt fence is falling over.

Starr said that he would send pictures to DENR. Then “the state would go out some time after I emailed them. They’d say here are the problems and nothing got fixed. It was an endless cycle.”

Starr would have liked DENR to have moved faster. But, Holley said, “the resources are always an issue. We have very limited resources and a large number of projects.”

The problems continued as DENR was reorganized—on Aug. 1 the state’s stormwater division — which is supposed to protect streams from stormwater pollutants and runoff — was moved from the Division of Water Quality to the Division of Energy, Mineral, and Land Resources.

Initially, DENR had difficulty figuring out who owned which lots in the subdivision — in part because the proper paperwork had not been filed with DENR. Usually the landowner is responsible for the environmental damage.

“In this case, the larger developer that began a lot of the work on the site was the Fred Smith Company, then a lot of the lots were sold off to other developers,” Holley said.

DENR’s documents show the developers repeatedly acknowledged the problems and said they would fix them, only for DENR to find on their next visit that nothing had been done.

After a notice of violation is issued, and notice of intent to enforce is sent, then fines may be issued.

Matthew Starr / Upper Neuse Riverkeeper

Caviness and Cates was issued notices of violation in July and December and a notice of intent to enforce in August. The Fred Smith Company received a notice of violation in February.

Adams said that heavy rains this year have made it more difficult to prevent the pollution.

“The amount and speed of the rain is a major factor in trying to protect the site,” he said.

A Pattern of Inaction

Hendrick said with DENR’s new customer focus he is seeing, “A pattern of the inspector finding a problem, the contractor swearing that they’ll fix it, the state accepting the pledge, and the problem continuing.”

“Customer service—that has been the talking point since Skvarla took office,” he said. “But DENR should be serving the public by protecting the environment we share, not prioritizing those who, as members of a regulated industry, it views as ‘customers.’”

Starr said that DENR has “done a lot of handholding along the way with no incentive [for the developer to comply]. It would be like saying, ‘don’t speed,’ but then never issuing a speeding ticket.”

Hendrick said, “The reason this spot got attention was that the Neuse Riverkeeper brought this to the state and did not take no for an answer.”

Starr wonders why no one was ever issued a fine.”What’s the incentive to come into compliance if there is no threat of a hammer.”

He said it was like DENR allowed the contractor to say, “Thanks guys we’ll take that under consideration.”