EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was co-produced with the Technician, N.C. State’s daily student newspaper. FULL DISCLOSURE: Tyler Dukes is an adviser to N.C. State Student Media.

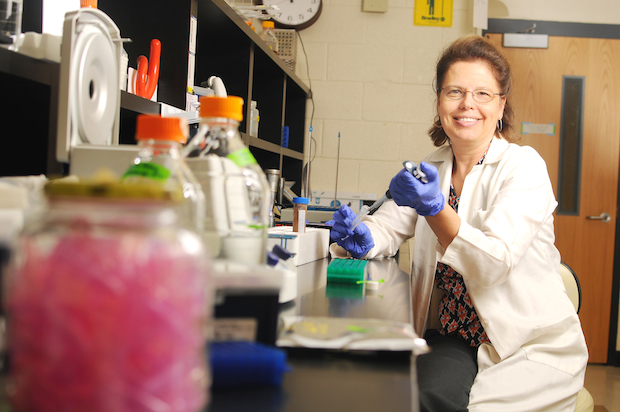

Lee-Ann Jaykus, a food science professor at N.C. State, received a $25 million grant from the USDA to conduct research on the norovirus, the cause of the foodborne "24-hour bug." | Photo by Jordan Moore/N.C. State Student Media

Story by Ankita Saxena and Tyler Dukes

When Lee-Ann Jaykus joined the N.C. State faculty in 1994, she was nervous about grants and thought she would be lucky to land one.

But after landing a five-year, $25 million grant from the USDA, she can certainly stop worrying about that now.

Jaykus entered the field of food microbiology when she was working toward her Ph.D. degree in the 1980s, and to her, viruses in food “sounded pretty novel and interesting.”

Now, she has one of the largest research grants ever awarded in the history of NCSU, which she’ll use with the help of 16 partner institutions around the country to research how to fight the common food-borne norovirus — a widespread pathogen known by most as the “24-hour bug.”

Jaykus said her research will eventually have significant impact on diagnosing infection, and will improve on methods used to detect contamination in food. It will also help the food industry better control the spread of these hard-to-kill microorganisms and educate food handlers on how to avoid food poisoning.

“Five years down the line, it will result in significant reduction of the day-to-day food poisoning cases we see,” she said.

The good, the bad and the ugly

When she took the job at NCSU, Jaykus said scientists knew about viruses in food but did not realize their significance. A 1995 paper by Paul Mead, an expert in bacterial and mycotic diseases, revealed viruses cause 87 percent of food-borne diseases, sparking a shift in focus for food microbiologists. It was an intriguing field for Jaykus at that time, and she has been researching long enough to watch it progress through the years.

Contracting norovirus typically isn’t serious, but it’s so widespread it ranks No. 4 in annual deaths by foodborne pathogens in the U.S. Here’s a look at how the top five measure up.

SALMONELLA

Pathogen type: bacteria

Symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

Cases: 1.03 million

Hospitalization rate: 27.2%

Death rate: 0.5%

Deaths:378

TOXOPLASMA GONDII

Pathogen type: parasite

Symptoms: flu-like

Cases: 86,686

Hospitalization rate: 2.6%

Death rate: 0.2%

Deaths:327

LISTERIA

Pathogen type: bacteria

Symptoms: Fever, aches, nausea, diarrhea

Cases: 1,591

Hospitalization rate: 94%

Death rate: 15.9%

Deaths:255

NOROVIRUS

Pathogen type: virus

Symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

Cases: 5.46 million

Hospitalization rate: 0.03%

Death rate: Deaths: 149

E. COLI

Pathogen type: bacteria

Symptoms: Stomach cramps, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

Cases: 63,153

Hospitalization rate: 46.2%

Death rate: 0.5%

Deaths: 20

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control

“It was initially quite slow to develop, but now we are making pretty rapid progress,” Jaykus said.

The microorganisms Jaykus studies can be classified into good, bad and ugly. The good ones cause fermentation, useful for making wine, beer and yogurt. The ugly ones spoil food — bread mold for instance. The bad ones — like E. coli, salmonella and norovirus — cause food-borne diseases that can manifest themselves in the form of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

“I work with the bad guys,” she said.

The norovirus isn’t exactly the worst offender — its symptoms typically last for a day or so and only about three out of every 10,000 people affected are hospitalized. But as the most widespread foodborne infection in the U.S., it’s 5.46 million annual cases result in the deaths of about 150 people. That ranks it the fourth most deadly foodborne pathogen out of 31, beating out other, less common bugs like E. coli that can cause more serious health risks.

“If you look at the sheer number of cases [like E. coli], it’s pretty low. These are relatively rare diseases. But when they hit, they’re devastating,” Jaykus said. “Noroviruses are exactly the opposite.”

According to Jaykus, noroviruses are present on mollusks, shellfish, fresh produce and other items.

“[These include] ready to eat stuff which is normally handled by human hands, such as sandwiches, pastries and all the other common things you could get in a fast food joint,” Jaykus said.

As far as scientists know, the virus does not infect people through the respiratory tract, but part of Jaykus’ research will focus on figuring out exactly how it’s transmitted so easily — and why it’s so hard to kill.

Hard to handle

Its keen survival instinct is one of the reasons why the norovirus sweeps so easily through close-quartered places like college dorms, schools and cruise ships.

If an infected patient vomits in one of those places, for example, even thorough cleaning won’t help. The virus resists common disinfectants, ionizing radiation and can survive for weeks outside of a host. Jaykus said even hand washing, although effective, might only work because the water and soap are flushing the virus away instead of killing it outright. Jaykus said in the lab, they kill the microorganism with chlorine concentrated at 1,000 parts per million — a potentially lethal dose for humans.

Even immunity to one strain — and the norovirus has many — only lasts for about six months, Jaykus said.

“It evolves rapidly and tries to circumvent the host,” she said. “The virus is doing all this fancy stuff to survive and propagate.”

Despite its ability to run through our immune systems, the norovirus has so far proved impossible to culture in the lab. Scientists rely on clinical samples in the form of fecal matter from infected patients to conduct their research. But Jaykus said she hopes that will change as a result of her team’s research.

“It’s been underreported, understudied and under-understood,” she said. “I don’t think we know why it’s difficult to cultivate.”

A new approach

This grant will certainly mean a change in roles for the professor. It’s one of the largest in terms of research for NCSU in its history, according to senior research analyst Liana Fryer. Other five-year grants, like National Science Foundation’s $15 million award to the university’s smart grid research hub the FREEDM Center, fall short by comparison.

But the money, to be doled out at $5 million per year over the five-year project, isn’t just slated for NCSU. Jaykus is now the leader of a team of scientists from 16 universities and research institutions all over the country, from the Baylor College of Medicine to RTI International, based in Research Triangle Park.

That makes it stand apart from other kinds of grants, according to Stephen Beaulieu, director of the Risk Assessment Program at RTI International. His team is working on a predictive modeling system that will help the USDA and other scientists identify the best courses of action when it comes to controlling and preventing outbreaks.

“With most projects, there’s always a feeling that we just can’t go far enough. Although you can make progress, there are still a lot of unanswered questions that can be frustrating for researchers,” Beaulieu said. “For this particular grant, we’re really looking at all dimensions of this problem.”

It’s a mode of attack that makes the effort “a very applied research project,” Jaykus said.

“What’s most unique about this is it allows us to take the issue and attack it from multiple angles,” Jaykus said. “If you’re really going to have an impact, you have to have that model. Otherwise people are just working on different things and not talking to each other.”

The next step for Jaykus to focus on is setting up infrastructure, getting new staff members and new administrative offices.

Despite the seriousness of the virus research, Jaykus has a sense of humor about her work. The research group, which deals often in stool samples, has a container of “artificial poop” in their lab they like showing to visitors.

“I have tons of poop stories that would make you laugh,” she said.