When Edward Judkins first moved back to Raleigh in the 80s, the neighborhood around East Davie Street was the sort of place where you said hello to your neighbors.

By the 2000s, his corner near Freeman Street was prime real estate for prostitutes and crack dealers.

Edward Judkins Photo by Jennifer Wig

“You couldn’t sleep at night. Car doors slamming,” he said. “People came up from NCSU, Chapel Hill. Mercedes, Cadillacs, expensive cars, all races of people.”

Judkins began to complain, even creating a cardboard poster with pictures taken from his front stoop: prostitutes, crack dealers, gangs.

“It’s not nice for the neighborhood,” he said.

He began toting his poster around the city, talking to anyone who would listen about the neighborhood’s downturn.

Whether spurred by Judkin’s complaints or something else, the area began to change. The neighborhood just east of downtown Raleigh, known as the Thompson-Hunter neighborhood, has undergone a small revitalization in the past several years. Rundown houses once used to run drug operations are now renovated homes for families.

But as the historically working class neighborhood gets a makeover, some wonder if those living there will be pushed out through “gentrification with justification.”

RPD Progress

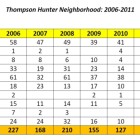

According to Raleigh Police, major crimes in the neighborhood have dropped from 227 in 2006 to just 78 so far in 2011. According to the 2010 RPD annual report, homicides in Southeast Raleigh were down to three from a high of 21 in 2008.

The Raleigh Police Department credits community policing with the drop in crime from its peak in 2008. Community policing began in Southeast Raleigh in 2009 and has since expanded to all districts.

Community officers differ from patrol officers in that their mission is to create relationships with residents and businesses within their district. While patrol officers are constantly running from one unknown call to the next, community officers work on a more structured schedule, investigating the source of crimes and building neighborhood relationships.

“Police stepped up their efforts a couple of years ago,” said Jason Queen, a realtor who works in the area.

One of the tactics was to park a large mobile unit, like a trailer, on a corner in the neighborhood.

“It completely changed the dynamic of the neighborhood when they did it,” Queen said.

The city’s Community Development Department was also a large part of the area’s recent changes. Using both federal and local dollars, the department razes condemned homes and pays to rebuild for single families of specific incomes.

Crews are doing some work near State and Bragg streets — a former hotbed for prostitution, gangs and drugs. The Martin and Haywood Street area inside the Thompson-Hunter neighborhood also had several houses renovated under city direction. Work in that area began in the early 80s, according to Michele Grant, director of Community Development.

“Part of what redevelopment aims to do is to make the living environment more stable and more attractive,” Grant said. “When you kind of move blighted influences, you’re also encouraging other development to take place. Certainly one of the discussions is how important community development has been not just in Raleigh but throughout the community.”

“Gentrification with Justification”

It’s not just the city making changes. Private developers have also successfully flipped houses in Thompson-Hunter. One of those houses, on East Hargett Street, sold for more than $300,000; the one next door sold for more than $400,000. Housing sale site Zillow.com shows homes between $75,000 and $224,000.

That type of change is not what the neighborhood needs, according to Daniel Coleman, chair of the South Central Citizens Advisory Council.

Coleman said redevelopment is great — as long as it doesn’t hurt the working class who live there. Aside from that, Coleman said focusing on single-family homes won’t help the city with its goal to create urban areas to live, work, and play, he said.

“When you look at the planning maps … where are the bars? Where is the vitality? Where is the Glenwood South? Why should we not have that?” he said.

As it’s happening now, the redevelopment is discriminatory “gentrification with justification,” he said, pushing out those who live there for the sake of improved economy and lower crime rates.

“But it defies even the idea that we’re trying to bolster downtown if we’ve got suburban development,” he said.

Queen said the price per square foot in the neighborhood has increased from $140 to $145 per square foot in 2006-07 to as high as $175 or $180 in some places now.

Of course, houses sold for $400,000 are not the norm. And thanks to the recession, that may not be an issue for awhile. Most nearby homes are valued in the low $100s. Some are as low as the $50,000 range.

Queen said those prices are “significantly lower than any of the six neighborhoods that surround downtown Raleigh.”

People have been speculating big change in the neighborhood for more than 25 years, said James Brown, owner of Brown Realty on New Bern Avenue. So far, they’re mostly still waiting.

The Raleigh native, whose dad started the business in the 70s, has served on the DHIC board and on the city Planning Commission. Brown said although there are signs of change, the area retains a stigma.

“It’s taken awhile,” he said. “As you can see, it’s still going on. I guess people are still skeptical.”

Some developers inquire, he said, only to hold back, unsure how the real estate market will turn around or when.

The “suburban feel” in an urban area Thompson-Hunter provides is appealing to some, Brown said.

Kate Whittier, 31, on the porch of her "new" house on Camden Street. This house had been abandoned before Whittier and her husband renovated it. Photo by Karen Tam.

That’s certainly the attitude Kate Whittier had when buying a house on Camden Street. She and her husband were deciding between the country and downtown.

She’s a teacher at Daniels Middle School and he works at N.C. State. The avid bicyclists wanted to commute without cars. They sought something affordable, which meant a condo wasn’t an option.

But when their realtor found an abandoned house a mere seven blocks from the original downtown border of East Street, they jumped at the deal. The renovations wrapped up this month.

“The neighborhood has character. The house has character. It’s everything we wanted,” said Whittier, who observed the proximity of greenway trails.

Her impression of the neighborhood is that it’s “a little more dangerous.” But “it seems to have turned around.”

She said she’s not worried about safety. Neither is Becky Semcer, who moved into a shotgun house on Camden Street in August 2009.

“It was obviously in a state of transition. There were a few things that made me a little nervous but I loved the house so much and the neighborhood so much,” Semcer said. “It had so much potential.”

She noticed a few hair-raising details: the rooming house across the street, some squatters. But she was reassured by a next-door neighbor who bought his house three months prior and had no problems.

“[I thought] if he can do it, we can do it together,” she said. “I was cautious, but never felt like someone was going to come into my house.”

Even in the year there have been changes, Semcer said. The rooming house has since been purchased by an older couple who is renovating it for their retirement.

“It has been amazing to me,” she said. “It’s really been a vast difference.”

Grant said there is always more community development work to be done, and pockets of not-so-great areas remain. But overall, their influence in Southeast Raleigh has been great.

“I’ve been here for awhile; it’s sometimes hard to get a sense of some of the things that really were here. But if you were see them, compare before and after, it really has been transformative,” she said.

That transformation and is exactly what Judkins wanted. Fighting for those changes wasn’t easy, he said. During the rougher times he often found bullets on his front lawn and was threatened for speaking out.

Now, most of the crimes you hear about are petty theft, said Lindsay Jordan, president of the Thompson-Hunter Neighborhood Association. She moved to a home on Hargett Street in August 2008.

After someone stole her garden hose, she began locking things up. Her white rocking chairs are chained to the front porch.

It’s not something you’d see in Cary. Nor are some of the residents who live nearby. But Jordan isn’t bothered.

“I’ve always felt safe,” she said. “Knowing you see gang people is more sad than anything. The majority are just neighbors.”

Through the Thompson-Hunter Neighborhood Association, those neighbors create their own community, holding events such as holiday celebrations, block parties and cookouts.

“People are here because it’s close to downtown and they like that and are walking,” Jordan said. “I just feel like it’s a great neighborhood and everyone is friendly.”

But what Coleman wonders is: can an area be cleaned up and made neighbor friendly without some negative change to those living there?

“Is the city of Raleigh pushing people out to the rims to make room for [other] people?” he said. “We’ve decided there are expendable people in this country. We don’t want to see them. Where do they go?”

“Yes there have been changes and there have been positive changes,” he said. “Change is a constant thing we have. We just have to be careful. We are making it very difficult for the working poor. We could leave the community in worse shape.”

Click image to view full size. Photos by Karen Tam.

- Many house in the area look like this work in progress on Hargett Street.

- The two houses on East Hargett Street that are now worth $300,000 and $400,000.

- A young boy rides his bike on Martin Street near the Haywood Street intersection.

- The view of some backyards along Haywood Street.

- Martin St.-Mark Hines, a U.S. Postal worker delivers mail on Martin Street. Hines said the area is much improved, that he “used to see police cars all the time, just sitting on the corner streets and now you see a police car just every once in awhile.”

- Looking downtown from Chavis Street.

- Homes under construction on New Bern Avenue.

- This empty house on Hargett Street sits across from two homes that sold for more than $300,000.

- Kate Whittier, 31, on the porch of her “new” house on Camden Street. This house had been abandoned before Whittier and her husband renovated it.

- Kate and her husband are avid cyclists. Their bikes stand ready on the porch.

- A man walks his dog down Chavis Street with a view of downtown Raleigh behind him.

- Sunflowers grow along a fence on Haywood Street.