More than a quarter century ago, Raleigh officials set out to encourage a new urban center, near highways, near the airport and on the other side of a large state park away from the city’s existing downtown.

What they got instead was Brier Creek, a wide-ranging suburban development with some high-density and mixed-use elements. It’s not quite the same as the suburbia that surrounds it, nor is it remotely as distinctive as city officials first intended.

Ted Strong

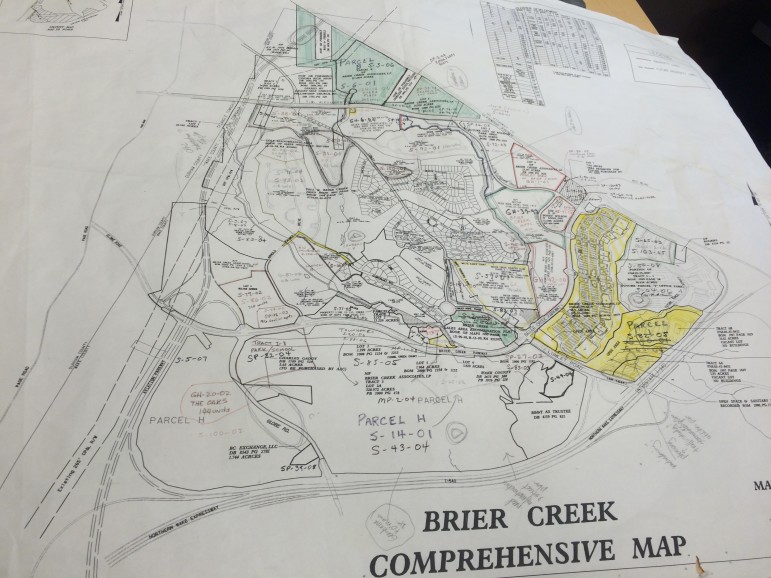

A map of the plans for Brier Creek

“We were trying to create a more walkable, urban-style environment,” said George Chapman, who was the city’s planning director from 1981 to 2005. “I’m not sure how terribly successful we were at it; there are parts of it that are.”

Planners also wanted to put in a rail transit system that would include a loop to the airport and Brier Creek connecting to a main line between Raleigh and Durham, Chapman said.

But the political will for such a system didn’t exist at the time.

“That, of course, has not materialized and doesn’t look like it will,” Chapman said.

The city’s plans were driven by the long-term needs of the area, but the realities of development helped dictate what went up when the trees that once blanketed the site came down.

Traffic is a constant in Brier Creek

By the 1980s, Research Triangle park was thriving, with firms such as IBM and Nortel. But workers had to commute from nearby cities.

“Everyone was coming from Durham and Raleigh, primarily,” said W. Stacy Barbour, now a development review manager in the City’s planning department. He dealt with many of the approvals at Brier Creek as a young planner.

Ultimately, after numerous planning efforts at both the Raleigh and the regional levels, a decision was made: Raleigh would cede zoning authority in some areas of Wake County, to Durham, primarily those areas where water and sewer could more efficiently be sent in from Durham. Durham, in exchange, would do the same for areas that could better be served by Raleigh.

That decision worked well with Vision 2020, the long-range plan the city had adopted in 1988. It designated three “regional intensity areas” for focused, dense growth, said Chapman. The were downtown, the area near Triangle Town Center and the area that became Brier Creek.

By 1996 a request to rezone a 1,999-acre property, then known as “the airport assemblage” to allow high density development was before city officials.

At the time, planners hoped the area might sprout a large number of high-rise buildings. At the same time, those in the real estate community didn’t necessarily expect the area to take off the way it did.

“No one expected it to be as big as it was,” said Mark Parker, president of the Richmond Regional Association of Realtors.

As the decade drew to a close, the first plans for development took shape. Plans included a shopping center, and Toll Brothers got permission to build a golf-course community.

In about 2004, Brier Creek Associates filed a master plan for a development between U.S. 540 and Brier Creek Parkway. The roughly 300 acre project involved apartments, and thus high density.

James Borden

Much of Brier Creek’s development lies along Brier Creek Parkway, which intersects with Glenwood Avenue

Parker praised the way the commercial, residential and office space at the project have worked together.

“They’ve done a phenomenal job of blending everything into one,” Parker said.

Soon after, the recession hit. There was a “significant pause” in development in the area, Barbour said. That’s unfrozen in the last couple of years, with a number of hotels being erected lately, he said.

Parker praised the diversity of housing available in the area.

“You’ve got everything from … relatively reasonably priced condos … to executive homes,” Parker said.

Chapman said he wishes there was more affordable housing at the site. Given how big the project was and how blank the slate was to start, there ought to have been more included he said.

Still, he said, Brier Creek benefitted from the goals officials set for it.

“I think it’s better than it might have been, but it’s not what we envisioned,” Chapman said.

Brier Creek Shopping Center