Editor’s note: If you have any questions about the controlled-choice assignment plan feel free to post them on the discussion forum. We will be happy to answer your questions. If we don’t know the right answer, we’ll find out from Wake County schools for you.

The recently adopted controlled-choice assignment plan could change significantly, depending on the level of tweaks the new board majority carries out when it steps into power Dec. 6.

But understanding how the plan might change means understanding the plan as it stands now. The plan is, as questions of board members and the public have belied, extremely complicated.

In two later segments of this series we’ll go more in-depth on the assignment plan, but first let’s simply take a look at what it is and how it works.

In the controlled-choice plan, the Wake school system creates a list of schools for families based on where they live. For families entering elementary school, that list will contain at least five choices. High school and middle school choice lists will be smaller.

Families who are already in the system do not have to participate in the choice process. However, they can choose to participate as frequently as every year.

For most elementary students, the list will contain at least two traditional calendar options, two year-round calendar options and one “high-achieving” school, dubbed “regional choice options” in the plan. Parents rank the choices in order of preference.

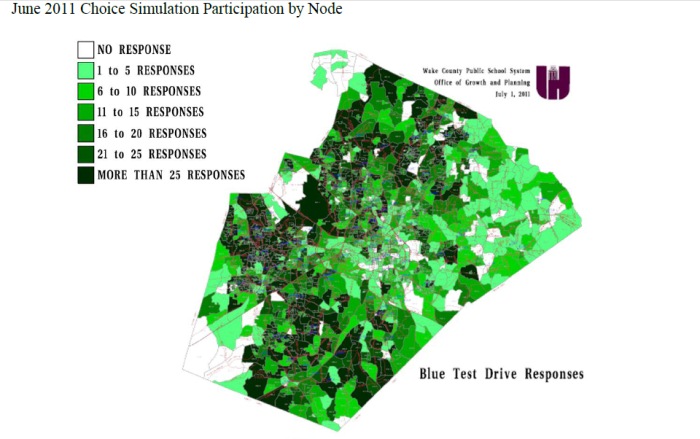

Superintendent Tony Tata’s assignment task force found that based on a test drive of the plan conducted earlier this year, parents chose schools for reasons of proximity and calendar choice much more than achievement.

Parental preference is also likely to be affected by which schools become more and less desirable over time. This could lead to some schools being under-chosen and some being over-chosen, which means fewer families will get their school of choice.

Capacity, Capacity, Capacity

The guiding force in deciding where a child gets accepted into school is capacity.

About 11 percent of schools in Wake are overcrowded, which is defined as exceeding 110 percent of a school’s capacity.

In theory, the plan will eradicate overcrowding, “but it will happen really slowly,” said assignment task force member Brad McMillen. “We’ll start from kindergarten such that we get every school back within the walls of growth.”

Here’s how it works:

Starting next school year no kindergarten class at any given school will be assigned an amount of students above its capacity.

That means it could take as long as 12 years to completely wipe out overcrowding. However, assignment task force members say overcrowding will decrease gradually during that time.

Because no class is allowed to exceed its capacity, the assignment task force developed a selection process for choosing students when a school has more applicants than seats.

Priority 1: Incoming siblings of current WCPSS students

Priority 2: Students who live within 1.5 miles of their first-choice school

Priority 3: Students whose nearest school is more than 1.5 miles from their home and who select that school as their first-choice school

Priority 4: Group 2 Proximity and Group 3 magnet students rising into 6th or 9th grade that have attended a Group 2 or Group 3 magnet elementary school whose first choice is the magnet middle or high school for their magnet program pathway

Priority 5: Students residing in a node designated as “low-performing” whose first-choice school is a regional school choice (R1 or R2)

Priority 6: Students residing in a node designated as “high-performing” whose first-choice school is a magnet school and/or is located in a low-performing area

Priority 7: Students attending a year-round elementary school whose established feeder pattern does not feed to a year-round middle school who select a year-round middle school

Priority 8: Students whose nearest school is severely overcrowded and select a school that is not overcrowded as their first choice

Each student will receive a sequential lottery number at random.

“Each student’s sequence number will then be increased by a set amount based on the priority categories that apply to that student for any given school,” the plan reads.

Starting with the highest number, students would be accepted into the school one-by-one until no seats remained.

The priorities were developed by staff based on school board policy 6200. It was revised by the neighborhood schools majority in May and made proximity, not diversity, the most important factor in student assignment.

However, the plan is critical of what the majority called for, which is a “rigid base assignment plan.” Such a plan would lead to “extensive overcrowding” and “significant under-enrollment” and would “continue to require regular reassignments, as it did in the past,” the plan states.

Accordingly, the task force factored proximity into assignment through the list of priorities, but distance is far from the plan’s be-all, end-all.

Lottery number + Priority number = Assignment

By way of example, let’s say a family participates in the second base selection process (Round Two Choice Selection Period.)

Their first choice is the highly demanded (and fictitious) Imaginary Elementary School. IES has 800 available seats, but 600 of them were taken during the first base selection round.

Three hundred fifty families select IES as their first choice in the second round, but only 200 seats remain.

Magnet Choice Application Period:

Dec. 5-19

Round One Choice Selection Period: Jan. 17- Feb. 24

Round Two Choice Selection Period: March 19- April 9

When the selection period ends, each child is assigned his or her random lottery number, the higher the better. Then, if the child falls into any one of the seven priorities, it will add to the number.

The 200 children with the highest numbers will be accepted into Imaginary Elementary.

The other 150 will be assigned to their second-choice school, unless it also has more applicants and seats. The same equation would then be applied.

It’s not a Diversity Policy, It’s a Capacity Policy

Interestingly, the plan points out a statistic aside from capacity, which may not bode so well for Wake County.

As of the 2010-11 school year, Wake County had 36 schools (22 percent) with more than 50 percent of children receiving free-and-reduced lunches — what many advocates term a high-poverty school.

The total percent of students who receive free-and-reduced lunch county wide is 32.4 percent, suggesting a fairly uneven distribution of those students already.

In one sentence, the plan states it will “mitigate these kinds of situations,” but later states the percentage of these high-poverty schools “should remain fairly stable over time.”

In other words, they won’t be reduced, despite the plan’s own admission that “high-poverty schools … have difficulty recruiting and retaining teachers” and that such schools “require more resources over time.”

Changing the order of the priorities could be a very real possibility for newly elected board members, who more forcefully support balancing achievement in schools.

Say, swapping priorities two and three with priorities 5 and 6 and giving more weight to achievement over proximity.

At least on the surface it seems like it would be easy for everyone except the software programmers.

But even if the priorities get swapped, the more important factors in where your child goes to school will be balancing capacity and a little luck of the draw when it comes to lottery numbers.