City officials want to once again spread treated sludge on city fields in the same area that once caused contamination of local wells. But this time, officials say they have learned from their mistakes.

On April 25, staff members from the Neuse River Wastewater Treatment Plant presented the outline of their proposal to spread treated sludge on 393 acres near the facility. The city has not spread treated sludge on this land since 2002, when it was revealed that over-application had likely caused groundwater contamination.

Wastewater treatment plants convert waste into two basic products. Raw sewage is treated and comes out as water that is either reused for irrigation or is discharged into the Neuse River. The other output is sludge.

Raleigh pays a company to take about 30 percent of their untreated sludge and process it into compost. The remainder is processed by the city into class A or B biosolids. “Biosolids” is an industry name for the solids that come out of the sewage treatment process. Some municipalities send this material to a landfill. Raleigh recycles it as fertilizer.

At Raleigh’s Neuse River facility, about 60 percent of the sludge is converted to class A biosolids that can be used anywhere as fertilizer. Roughly 10 percent is converted to class B biosolids, material that contains detectable levels of pathogens and can only be safely applied to fields not used to produce food for people.

Raleigh is requesting a permit to spread class B biosolids on their fields near the plant, instead of paying to truck them to eastern North Carolina. Raleigh assistant public utilities director T.J. Lynch estimates the change could save the city around $500,000 per year. However, the request is complicated by the fact that the groundwater at the site is still contaminated with nitrates.

City officials planned to submit their application to the state last week. The state Division of Water Quality will have 90 days to respond, and the process will include a 30-day public comment period. A decision is not likely until late summer at the earliest.

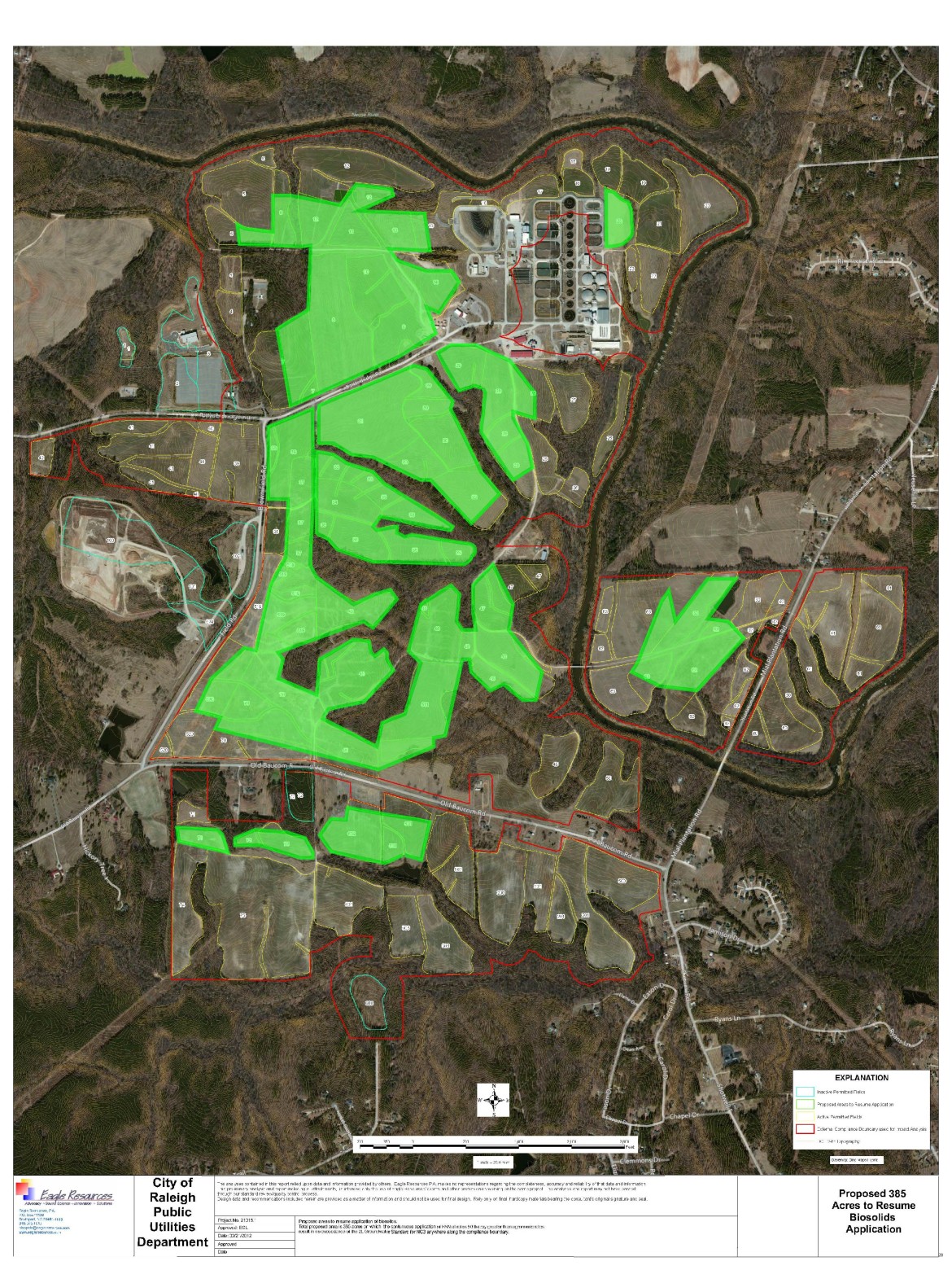

A top down view of the area surrounding the plant. The city would like to spread biosolids on the fields shown in light green.

Local Wells Contaminated

In 2002 an ex-employee of the treatment plant contacted the Neuse River Foundation riverkeeper to report that the city had been over-applying biosolids to their fields. A subsequent investigation by the state found high levels of nitrates in local wells.

As an outcome of the investigation, the city paid a $72,500 fine and agreed to repair the damage.

Excessive nitrates in a water supply can reduce the blood’s ability to carry oxygen to tissues. In children under six months of age, it causes blue baby syndrome, which can be fatal.

Several residential wells in the area were deemed unfit for use. In response, Raleigh routed city drinking water to 39 residences and will provide water to those homes at no cost for 20 years.

Lynch said, “That was our way of rectifying a problem that we created.”

Though, he said, “that’s always been an agricultural area out there, so whether those nitrates were from us or not, we took on that responsibility.”

The city also constructed three wetlands to reduce the nitrogen in the groundwater flowing to the Neuse River and pumps water from two wells to the treatment plant to remove nitrogen.

In addition, the city changed how it operates the wastewater treatment plant.

Matt Fleahman, environmental engineer with the state Division of Water Quality, said sludge applications now will not result in the same outcome.

“Things have changed significantly with the city,” he said. “What happened there 10 or 20 years ago would be impossible under the management and policies in place today.”

The treatment plant has won platinum awards from the National Association of Clean Water Agencies for operating within the limits of their permit for eight consecutive years.

Looking south over Raleigh's Neuse River Wastewater Treatment Plant.

What to do with treated sludge?

While recycling sewage seems like a much better choice than burying it in a landfill, the practice remains controversial around the nation.

“Things like metals and pharmaceuticals are a problem nationally, but there is not a readily available solution,” said Alissa Bierma, riverkeeper for the Upper Neuse. “Until we can figure out how to keep those things out of the sewer, they are going to be in the sludge.”

Raleigh’s sludge contains less than one quarter of the federal standards’ strictest levels allowed for metals like copper and arsenic. The city achieves such low levels by requiring industrial sources of these types of contaminants to treat their water before sending it to the plant.

There is not a federal standard at this time for pharmaceuticals in wastewater.

Lynch said that if the sludge is handled properly, it should not smell bad when applied to the fields. In response to complaints from neighbors, the plant no longer loads trucks early in the morning, when cool air can trap odors at ground level.

Regardless of whether the biosolids will add any smells, the air around the plant isn’t roses, according to Tonya Debnam, whose family has owned property just east of the plant for 80 years.

Her well was contaminated last time, and she smells the facility daily.

“Every day we smell them, and we call them and say, ‘You’re smelling really bad,’ and they ask what it smells like and I say, ‘What do you think it smells like?’”

Debnam knows the type of odor can help the city determine the source. Lynch said the city has invested in equipment to improve the ability to inject oxygen into the sludge, which helps organisms break down the material more completely and reduce odors.

Bierma is waiting to see the city’s formal application before deciding how she feels about spreading sludge.

“I am not 100 percent convinced that it can be done yet,” she said. “I have more to look at and learn. But they really have made significant changes and improvements to the plant and how it operates.”

Lynch emphasizes that times have changed and the city has learned “from the mistakes of our predecessors.”

“We went from a time with very little guidance on the application [of biosolids], and now have very specific information,” he said. “Inevitably there is going to be some nitrate that gets to the groundwater. Our intent is that that will be very little to none.”