Outside Jeffreys Grove Elementary off Creedmoor Road, Joseph Holt Jr. stood beside the school’s principal, watching students on the playground.

There was nothing terribly unusual about Holt’s visit. It was Spring of 1972, and fresh back from a three-year tour in Japan, the Air Force officer was planning to enroll his children at Jeffreys Grove. Nor was it unusual to see both black and white children playing together — almost two decades had passed since the Supreme Court declared segregation unconstitutional.

Yet Principal Aquilla Moore, whom Holt knew from his old Raleigh neighborhood, emphasized something special about the scene on his school’s playground.

“He kind of stood there and he goes, ‘You see? All these children are playing together and are just getting along fine,’” Holt said during in an interview last week. “He said, ‘I wanted you to see this Holt, because you’re responsible for this. If it hadn’t been for you, we wouldn’t have this.’”

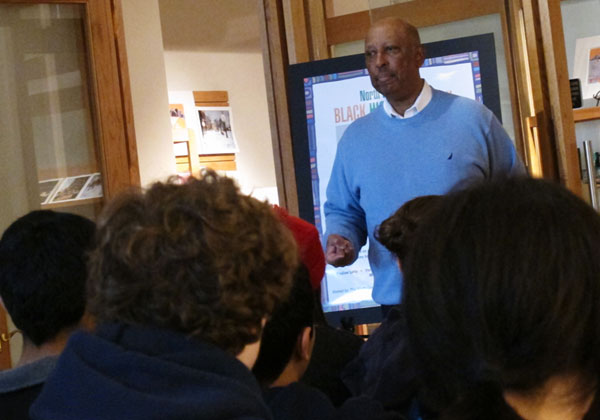

Joseph Holt Jr. answers answers questions from Raleigh Charter High School students after they watched a documentary on his effort to gain admittance to an all-white high school in the city. Photo by Tyler Dukes.

Every time he returned to Raleigh during his career in the service, Holt says he would hear a few comments like these from old friends, neighbors and fellow members of the black community. But he’d hear other comments as well, some from the same men and women he’d graduated with years earlier.

“[They’d] meet me, encounter me when I’d be home on leave some times and say, ‘Hey Joe, I remember. Yeah man, you graduated from Needham Broughton.’”

Then he’d have to correct them. He’d have to gently remind them that he never went to Needham Broughton High, an all-white school less than a mile from his house. He’d say that, in fact, he shared the commencement stage with the all-black class of Ligon High in 1960, a full six years after Brown vs. Board of Education.

But for most of Holt’s life, the story that whispered through the halls of his household needed its own corrections, its own gentle reminders of the nuanced world where a teenage Holt and his family fought to enroll him as the first black student at an all-white Raleigh school. Their attempt failed, and the courts said it was the family’s fault.

Holt would later find out, with the help of his daughter, that it was a little more complicated than that.

Making History

Although William Campbell made history in 1960 as the first black student in Raleigh to attend a traditionally all-white school, Joseph Holt Jr. was the first to try.

In August 1956, Elwyna Holt applied to transfer her son first to Josephus Daniels, right down the street from their home on Oberlin Road. School officials told her the application came too late, so the family waited a year to try again, this time at Needham Broughton.

According to court documents, Holt’s parents listed a few reasons they wanted their son at Broughton over Ligon. Aside from its closer location, they also wrote that Broughton offered a “fuller academic and extra-curricular program” and that the transfer would “remove the stigma of racial segregation.”

“When Brown vs. Board was handed down, that opened a door. In a way of speaking, much of the black race shouted, ‘Hallelujah, things are beginning to change.’ So we stepped forward,” Holt said last week. “We weren’t seeking notoriety; we were seeking first-class citizenship.”

A teenage Joseph Holt Jr. poses with his parents, Elwyna and Joseph Sr., in their home in Raleigh. Photo courtesy of Joseph Holt Jr.

Holt says he’s not sure he fully understood this at the time. Reserved and quiet as a teenager (Holt said his classmates would “probably say he was some kind of nerd or egghead”), his parents never really sat down with him for a serious discussion about what the fight would mean. Joe Sr. and Elwyna did what they knew what they needed to do, Holt said, and he trusted it was the right way forward.

“I knew it was significant because it would have been a dramatic change socially from what had occurred in the past,” Holt said. “But the full impact of what it would mean in time — I don’t think I thought of it in those terms yet.”

What he fully understood even as 13-year-old however, were the threats.

Soon after The News & Observer first reported the family’s initial application to Daniels in 1956, the calls and hate mail started coming to the house. Racial slurs and promises of violence, whether over the phone or hurled from passing cars, became a part of everyday life for the Holts.

“It was something that was intimidating, because you could never get away from it,” Holt said. “We were being mentally terrorized on a very regular basis.”

His father was fired from his job in what the family believes was retaliation, forcing them to rely heavily on Elwyna Holt’s pay as a schoolteacher. None of this sat well with Elwyna, who Holt said was troubled and nervous about what she saw and heard from members of her own community.

“She was very tense, but my mother deep down was a very resolute person,” Holt said. “I think she understood what this meant.”

They would need that resolve. Following the school board’s rejection of the then-sophomore’s transfer request, the family appealed the decision over the next three years all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the fall of Holt’s senior year at Ligon, the justices declined to rule on the case, just as they had many similar cases following their so-called Brown II decision back in 1955. Instead of settling these complaints one by one, they tasked district courts with the job of integrating schools “with all deliberate speed.”

That meant the lower court’s ruling remained unchanged. And after an entire high school career spent wondering where he’d be attending class the next day, Holt finally had his answer. There was a small sense of relief there he’s only recently begun to talk about.

“In ’59, I was sitting on pins and needles, as we had been for years. What’s going to happen now? Suppose there was a ruling made by the Supreme Court that I should immediately be admitted to Needham Broughton High School?” Holt said. “I would never have said I wanted to stay at Ligon. I never would have said it, because it would have devastated the entire effort. It would have smashed it.”

But that relief also brought a sense of personal failure.

In its affirmation of the district court’s ruling on the Holt case, appellate judges wrote in 1959 that they didn’t want their decision understood as “approving the deliberate segregation of races in public schools.” They acknowledged that Raleigh’s school assignment policies “tended to perpetuate the system.” They even noted that, in sworn testimony, members of the Raleigh school board said race was a factor in their decision to reject the Holt application.

Despite all that, the appeals court agreed with a lower court that the Holts had not “exhausted the remedies afforded them by the statutes of the State.” Specifically, they had failed to appear in person before the school board back in 1957 — an action the family argued was not required by the law governing student reassignment.

According to court documents, the board wanted the Holts to provide more information, including why they thought Ligon was, in the court’s words, “inferior.”

But to the Holts, the prospect of appearing before the board smacked of intimidation. Amid all the threats, the newspaper coverage and retaliation, it was one thing they weren’t willing to put their son through.

“Why should any kid have to be made to jump through all these hoops? Why? Why are you going to have a kid be interrogated before a school board?” Holt said. “That’s not right. That shouldn’t happen.”

So they didn’t go. The application was denied. And when the case ended three years later just short of the Supreme Court, the understanding was that the Holts had failed — and it was all their fault.

That narrative rippled through the Raleigh community, black and white. And it settled on the quiet, reserved teenager still in his senior year of high school.

“It’s one thing to be an individual carrying that kind of weight,” Deborah Noel, one of Holt’s three children, said. “It’s another thing to be Joe Holt and carry that kind of weight.”

Holt graduated in June 1960, second in his class — but his diploma said Ligon, not Broughton.

“I did have mixed feelings,” Holt said. “Had I achieved, or had I lost?”

A Complete Picture

Growing up, Noel said the story of her father’s struggle wasn’t something they talked about all the time. Any conversation on the topic was often short on details.

“It was just whispered,” she said.

Yet when she was finishing her master’s in television production at the University of Maryland in the early ’90s, she found herself hunting for a good documentary topic.

“One day he was talking about it and I was sort of humoring him saying, ‘Somebody should make a movie about that someday,’” Noel said. “And the lightbulb went on.”

She asked her father if he’d be willing to share his story in her documentary, and he agreed. Together, they worked to piece together a 40-year-old story from newspaper articles, school board minutes and interviews with the last surviving members of Raleigh’s leadership.

But she was worried. She knew the legacy of the story, the guilt it carried. She didn’t want to reopen old wounds or compound the injuries.

“I was concerned, because the understanding we had was that ultimately he wasn’t able to go because of a fault of his own,” she said.

Then she sat down with J.W. York, at that point in his early ’80s, who in 1956, had been a prominent developer and a member of the Raleigh school board. He’d voted against Holt’s application to attend Broughton. Noel asked York about her father.

“If Joseph Holt had been at elementary level and had applied at the same time William Campbell applied at an elementary school, he would have been accepted, I would say, absolutely,” York told Noel in the documentary “Exhausted Remedies.”

Joseph Holt Jr. speaks to a group of students from Raleigh Charter High School at the Raleigh City Museum Feb. 22. As a teenager in the 1950s, Holt became the first black student in Raleigh to request enrollment in an all-white public high school. Photo by Tyler Dukes. />

This, Holt said, was something new.

“Almost 50 years prior, no such comment was made, no such allusion was made to the fact that, ‘Well we just want to find somebody in the primary grades.’ They didn’t say that then. They just said, ‘denied in the best interest of the student,’” Holt said last week. “If that’s really what it was, if you were telling the truth, the fact that we failed to exhaust some administrative remedy didn’t have a damn thing to do with it. And it didn’t. They couldn’t afford to say that we were denying Joe Holt or anybody else on the basis of race, because that would have been in direct conflict of the Supreme Court’s edict.”

In fact, North Carolina’s leadership had taken elaborate steps not only to delay integration, but to explicitly dodge it. The General Assembly’s Pupil Assignment Act of 1955 granted local school boards the power to block the reassignment of black students on supposedly race-neutral grounds. In 1956, North Carolina legislators and voters approved a referendum called the Pearsall Plan to allow parents to opt out of sending their children to integrated schools and potentially close them down.

“The Pearsall Plan enabled school boards to be very arbitrary, to be duplicitous and evasive without being held accountable,” Holt said. “That’s exactly what the Raleigh school board did and a number of other school boards throughout North Carolina.”

These measures weren’t struck down until 1969, years after Holt had moved on to graduate from St. Augustine’s College and earn an officer’s commission in the U.S. Air Force.

“What we discovered was that it wasn’t the family’s fault at all,” Noel said. “There was a policy in place, social structures in place, laws — all of this influenced the outcome of this single story.”

Noel said the realization was an amazing feeling for her father, akin to learning you lost a championship to a bad call rather than your own failure.

“It doesn’t change the outcome of the game, but it does change how you feel about it,” Noel said.

Walking Across the Stage

A lot has changed for Joseph Holt Jr.

He says he’s still haunted by the misperceptions that plagued his family’s story for so long, by the cheery, ubiquitous narrative of Raleigh’s peaceful integration process years and years after Brown v. Board. He’s seen that narrative refined somewhat by efforts like Noel’s documentary and Civil Rights exhibits at the Raleigh City Museum.

But for a long time, what Holt still sought was a wider recognition of his family’s struggle, the kind that would grant him and his parents the same sort of pioneer status historians grant Bill Campbell. That came in 2006, when his mother and father were inducted to the Raleigh Hall of Fame, just one year after the Campbells.

That was “the highlight of it all, he said.

But he’s tasted that recognition before, the night he walked across the stage as salutatorian of Ligon High, accepted his diploma and politely shook the school board chair’s hand. From the all-black crowd — neighbors and friends who had seen his picture in the paper, heard about the rocks and insults lobbed at his home and extended their support with silence — he recalls a thunderous ovation.

“I could sense that there seemed to be an applause that reflected the pride of the audience in what I represented,” Holt said. “I had led the way. I had fought the system.”