If hydroelectric comes to Raleigh, it won’t be by way of the Falls Lake dam.

City Council members this week decided to end a study of a hydroelectric dam at Falls Lake. The dam would not have created much energy, and it would have taken 50 years to recoup the costs from selling the electricity.

Assistant Public Utilities Director Kenny Waldroup, who recommended ending the project, said the city had to make sure the project was socially, economically and environmentally viable before it would be considered.

While staff decided that it had a lot of support from the community and wouldn’t be a detriment to the environment, the numbers just didn’t work out.

“We have a fiduciary responsibility to ensure that any investment we make has a reasonable financial risk,” said Waldroup, “and the project, as attractive as it is, just didn’t have a reasonable financial risk.”

Even with favorable financing conditions, Waldroup said, the project would take 50 years to pay for itself. That’s 20 years longer than the term of the bond that would be needed to fund the equipment.

Making the project less appealing are possible state and federal changes to how alternative energy is funded, credited or purchased.

The natural gas boom has also decreased energy costs, Waldroup said, and it has made investing in alternative energies more difficult.

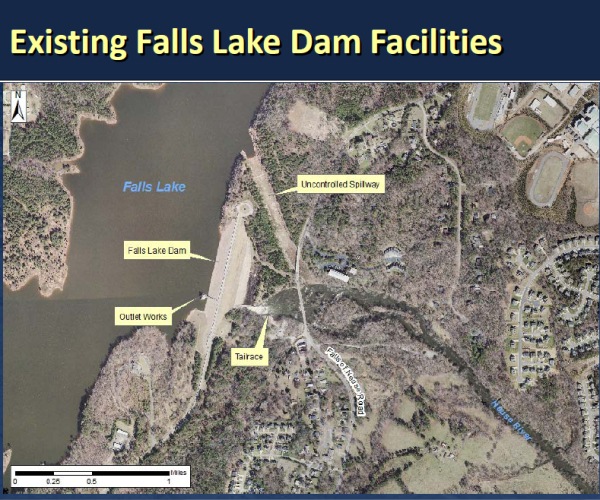

The city began investigating hydroelectric at Falls Lake in 2009 when private power company called Community Hydro, LLC submitted an application to FERC for its own permit. Since Falls Lake is used as one of Raleigh’s primary water sources, the city wanted to keep private interests away from public water and filed for a competing permit, which it was awarded in late 2010.

Since then, the city has spent about $300,000 in researching the feasibility of using the dam for power.

Waldroup said the city often spends money investigating projects that could have a potential cost savings.

“There are examples of successful investigations that have reduced cost. This just wasn’t one of them,” he said.

The dam is operated by the Army Corps of Engineers, which monitors the flow for only five Congressionally regulated uses: fish and wildlife, recreation, water supply, water quality and flood damage reduction.

Because producing electricity isn’t one of those permitted uses, the rate at which water goes through the dam would stay the same. Getting the extra revenue or savings from the generated electricity would only be a perk.

Waldroup said it’s unlikely that a private energy company would sweep back in to build a project that would see a payoff 50 years down the road. Typically, a reasonable time for an investment is three to seven years. He said that there are some hydroelectric companies that are in it for the long haul, but even those companies expect to see a return in 20 years.