Raleigh certainly loves its chocolate.

Especially when it is grinded, mixed, flavored and packaged locally by hand, with cacao beans sourced directly from farmers in Venezuela and Costa Rica.

The city’s first bean-to-bar chocolatier, Escazu Artisan Chocolates of Mordecai, is reaping the benefits of a growing love affair—locally and nationally—with artisan food. Sales now top $500,000 annually, so much that chocolatiers Hallot Parson and Danielle Centeno are forced to turn business away.

Danielle Centeno, Escazu co-owner, holds “push up pops” — ice cream made with their chocolate. Photo by Karen Tam.

There’s simply not enough space at 936 N. Blount Street to produce any more chocolate.

“If Whole Foods wanted us nationally instead of just in the Southeast, we couldn’t do that without increasing our production immensely,” said Centeno, a pastry chef who runs the confections and retail operations. “And we couldn’t do that here.”

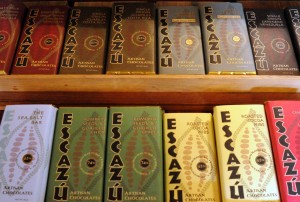

Too much business isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s helped Escazu hire nine workers, pay off its first business loan (secured when it moved from Glenwood Avenue in 2009) and operate profitably for the first time. It’s let Parson and Centeno master their current operation—winning 2012 and 2013 Good Food Awards and recognition in Southern Living and Wine Spectator magazines. Escazu now distributes its eight bars to specialty markets and retail stores nationwide.

The retail shop, with a hot chocolate bar, hand-made decorative confections and ice cream each day, has become a neighborhood staple.

“People are looking for quality and are willing to pay a little more for that,” said Parson, who made his first chocolate bar in 2005.

The quality of Escazu and other bean-to-bar chocolate comes from a process 100 years old or more that starts with a farmer of cacao in some tropical climate. Parson built a relationship with a Costa Rican farmer (Escazu is named after a town there) and Centeno brought her ties to her native Venezuela. They now import three or four tons of beans at a time from those farms. The beans are sorted and roasted in an antique coffee roaster they bought and shipped from Spain.

Hallot Parson, Escazu co-owner, checks the consistency of the chocolate as it is mixed in the 1930s machine he bought in Spain. Photo by Karen Tam.

About 180 pounds of nibs are then ground into a liquid, and sugar (and sometimes cocoa butter) is added to meet a certain percentage of cacao. The chocolate is aged, and later, tempering machines heat and cool it to achieve the perfect appearance and texture.

Ingredients such as pumpkin seeds and chipotle chili are added just before the chocolate goes into a mold. Sea salt is sprinkled after. Bars are then wrapped and labeled by hand, about 100 per hour.

Escazu produces 200 to 400 bars on a slow day and 1,600 to 1,700 daily before holidays such as Christmas and Valentine’s Day.

Centeno’s small team of chocolatiers produces about 87,000 truffles a year for the retail shop. Daily, they bake cookies and make ice cream and introduce specialty treats.

“It’s frustrating,” Parson said. “We can see so many avenues for growth.”

Escazu chocolate bars. Photo by Karen Tam.

Bean-to-bar chocolatiers have grown in number since 2005, when a Colorado man named Steve DeVries opened the first shop in Denver. Escazu was among a dozen or so chocolatiers nationally when Parson opened the first retail shop in 2007. Today, bean-to-bar chocolate is one of eight categories included in the Good Food Awards, a three-year-old competition to recognize U.S. producers of craft food. For the 2013 awards, 67 chocolate makers entered.

“Part of the popularity of these bean-to-bar manufacturers is that they are local, maybe the ‘new’ local chocolate shop,” said Susan Smith of the National Confectioners Association. “They bring with them a certain amount of hometown pride … since they sell the products they make in the back of the store right up front.”

Escazu’s success has allowed it be picky about the future. The partners recently quashed plans to move alongside Market Restaurant and Yellow Dog Bakery in the Person Street retail center two blocks away. Developers failed to meet Escazu’s timeline. Now, they’ll wait until the right deal comes along.

A lease was renewed for another year in March. They hope to self-finance the move when the right property becomes available.

Parson and Centeno hope to double the existing 1,600 square feet. They’d like room to add more equipment sourced from overseas and a larger retail shop and hot chocolate bar to serve loyal customers and attract even more.

The inside of Escazu, located on Blount Street. Photo by Karen Tam.

They plan for more storage and prep space, and sophisticated and professional décor this time around. And perhaps someone besides Parson will operate the forklift required to move the roaster and grinder.

“It will be a place that will allow us to make as much as we want to make and grow as much as we want to grow,” Centeno said.