This story is the second of a two-part series about Raleigh’s efforts to protect its water supplies from nutrient pollution and sedimentation. Part one looked at the city’s efforts to prevent individual septic systems from contributing nutrients to the watershed.

During the last session, the General Assembly eliminated the land conservation tax credit, consolidated two of the state’s four land conservation trust funds, and continued to cut funding the Clean Water Management Trust Fund.

Because of those actions, nonprofits and the city of Raleigh will now bear more responsibility for the protection of water supplies.

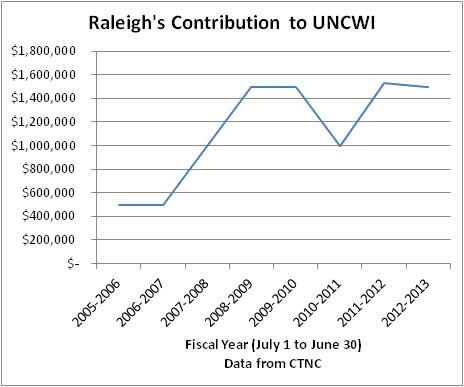

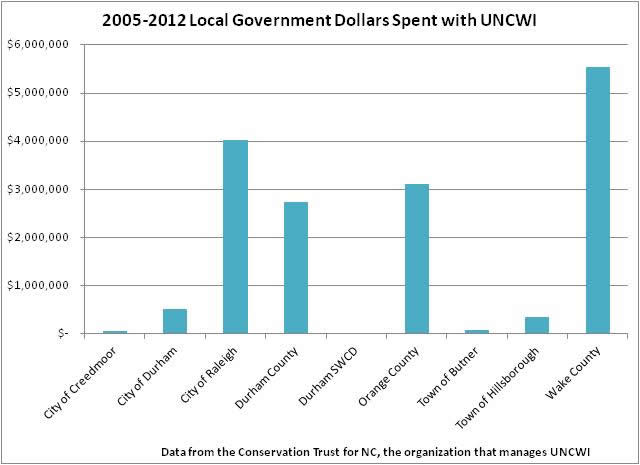

The City of Raleigh has worked with the Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative (UNCWI) since helping found it in 2006 to protect land near the city’s water supplies.

Protecting land near water supplies reduces nutrient pollution and the amount of sediment flowing into the reservoir — sediment that can reduce the amount of water the reservoir holds.

Past land protection projects often relied on matching funds from federal, state, local and nonprofit sources. In June, the Conservation Trust for NC (CTNC) reported that Raleigh has leveraged its dollars at a rate of 16 to 1, investing $3.15 million in 29 of the 63 projects completed since Upper Neuse Initiative’s inception.

- Source: CTNC.

- Source: trusts’ 990 tax forms.

- Source: annual reports.

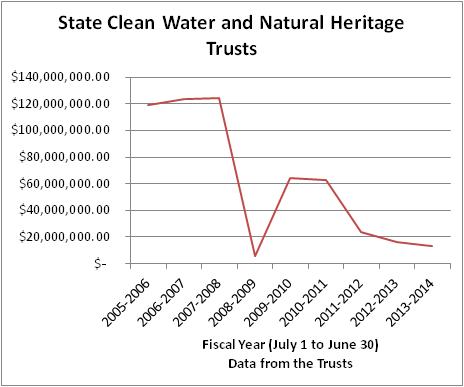

But since 2009, when Gov. Bev Perdue took $100 million from the Clean Water Management Trust Fund to help balance the state budget, state spending on land conservation has been reduced.

Clean Water Management Trust Fund funding is at one-tenth of historic levels, and Richard Rogers, executive director of the fund, said he does not expect the funding to return to its former, legislatively-mandated level of $100 million per year.

The legislature in 2011 removed that portion of the law that created the fund. Meanwhile, the Natural Heritage Trust Fund also has been merged into the Clean Water Trust.

“When we had more funding for both trust funds, it made sense to have two separate entities that had separate missions with boards that focused on those missions, but as funding has decreased, at a certain point it makes more sense to combine them for efficiency,” explained Lisa Riegel, executive director of the Natural Heritage Trust Fund.

The state also eliminated the land conservation tax credit — a tool that nonprofit land trusts relied on to encourage landowners to protect land. The credit allowed land owners to write off 25 percent of donated land value on their taxes during a 5-year period.

North Carolina was the first state in 1983 to offer a land conservation tax credit. Sixteen other states now offer some form of credit. North Carolina is also the first state to repeal the tax credit.

All of these changes mean Raleigh officials may need to reconsider how they uses revenue from the watershed protection fee, begun in 2011, that has previously been used for land preservation and stream restoration in the Falls Lake and Swift Creek watersheds.

Raleigh Public Utilities Director Kenny Waldroup said legally, the money can be spent in other ways, but it’s not preferred.

“Of course we did write that watershed protection fee broad enough to pilot projects to remove nutrients at point source sites,” he said. “But we want to focus on a watershed protection approach.”

The watershed protection approach includes land conservation. He emphasized that City Council approval is required for any use of watershed protection fee money.

An Example: Land Conservation in the Swift Creek Watershed

In December of 2012, Raleigh purchased the Blackcap property on Windy Beech Lane in Garner. Buck Branch Creek, a tributary to Lake Benson, one of Raleigh’s two drinking water reservoirs, flows through the property.

“We captured that failed subdivision during the record economic downturn when it was reasonably priced, and we look at it as an opportunity not only to restore right next to our water supply, but what can we do here, if anything, to create a demonstration project to capture, treat and remove pollutants,” Waldroup said.

Dan Riechers / Raleigh Public Record

The Blackcap Property

The Blackcap property was acquired entirely with Raleigh watershed protection fee dollars and with the help of The Triangle Land Conservancy.

The city acquired the 27 acres valued at $529,800 for $322,300. The landowner donated $207,500 in land value and can use the 25 percent tax credit during the next five years, saving $51,875 in state taxes. The Town of Garner agreed to manage the property and included it in their greenway plan.

The Land Conservation Tax Credit

The General Assembly’s elimination of the tax credit removes a tool that land trusts often relied on to help landowners decide to protect land.

The credit could be taken during five years at a maximum of $250,000 annually for individuals and $500,000 for corporations. It has helped set aside more than 230,000 acres of land since 1983 and often was used with other funding to protect land at a fraction of its value.

A tax credit provides a reduction of tax owed, making it more valuable than a deduction, which only reduces the amount of income on which a person or business is taxed. The land conservation tax credit cost the state about $17 million per year.

William Flournoy, executive director of the Triangle Greenways Council, said the donor “had still given away 75 percent of the value of the property so no matter how you cut it, [the tax credit] was still a good deal for the public.”

In other words, for $17 million per year, the state was protecting $68 million worth of land.

“We are going to have to figure out how to do business differently because we’ll have to find a replacement for that match,” Flournoy said.

Edgar Miller, government relations director with CTNC, said it’s a huge loss.

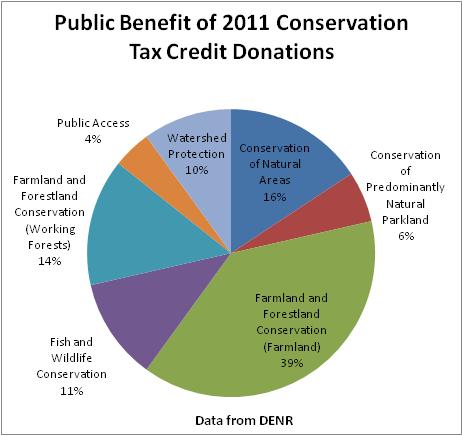

“Over half the deals in recent years have been for family farms and forest land—keeping our rural landscape and forest lands available for forestry,” Miller said.

Rogers said, “I’m extremely sorry to see that go and I hope that there is an effort to get it put back at some point.”

The legislature did not single out conservation—eliminating or expiring a few dozen tax credits and deductions this session, according to Miller.

Donors remain eligible for the charitable contribution and federal tax deductions for any donated land, Miller said.

“We are pleased that they did not put a limit on charitable deductions, because if they had put a cap at $10 or 15,000, most gifts of land would far exceed that,” he said.

CTNC announced Aug. 26 that it was offering $1.2 million of its own funds, up to $25,000 per property, to help cover transaction costs for local land trusts as they rush to complete deals before the credit expires Dec. 31.

Reid Wilson, executive director of CTNC, said that deadline will make things difficult.

“Land deals don’t take a week or two,” he said. “They take months. So I think a lot of land owners and land trusts are going to be working really hard for the next few months.”

Flournoy said that Triangle Greenways has identified 18 projects including some on Little Lick and Lick creeks in the Falls Watershed and have notified land owners that the credit will be expiring.

Waldroup said that it is too soon to say what the city’s response will be to these changes, but said, “We will find ways to invest [the watershed protection fee] to continue to protect our watershed. We will look for the best value for that investment.”

Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative

The Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative, begun in 2005 by then Raleigh Mayor Charles Meeker, the Conservation Trust for North Carolina, and other partners, identifies and protects lands critical for the long-term health of drinking water supplies in the Upper Neuse River Basin.

Caitlin Burke, special projects and grants coordinator with the Conservation Trust and UNCWI coordinator, said the thinking was, “What we need to do is something like what New York has done in the Catskills, protect our water supply.”

The Upper Neuse includes drinking water supplies for Butner and Granville County, Durham, Creedmoor, Hillsborough, Orange County, and Raleigh and its surrounding communities.

Conservation trust partners:

Conservation Trust for North Carolina

Ellerbe Creek Watershed Association

Eno River Association

Tar River Land Conservancy

Triangle Greenways Council

Triangle Land Conservancy

The Trust for Public Land

Raleigh’s investment of $4 million since 2005 has protected $65 million in land value and 2,785 acres along 33 miles of stream, leveraging 16 dollars for every dollar spent.

“The biggest problem that we might be facing right now is related to the end of the conservation tax credit and state funding in general,” Burke said. Without matching funds, “the city of Raleigh has to pitch in a little bit more.”

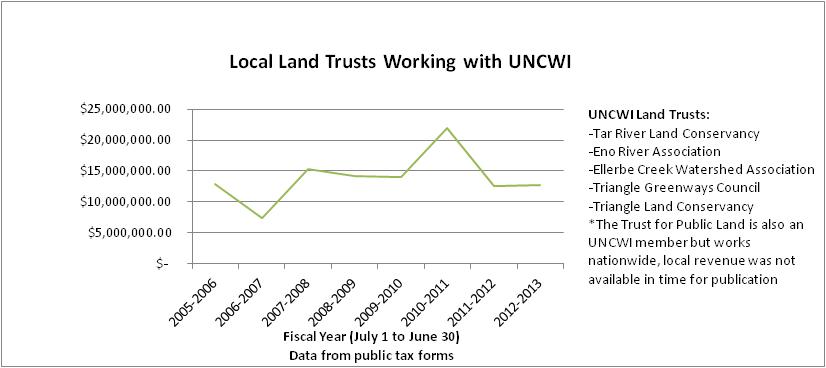

Reduced state funding may jeopardize the health of the land trusts, she said. Land trust revenue has been down some in recent years but they have continued to have successes.

Chris Dreps, executive director of the Ellerbe Creek Watershed Association, credits UNCWI.

He said, “you just don’t go out and find matches. So UNCWI has been a big part of that success.”