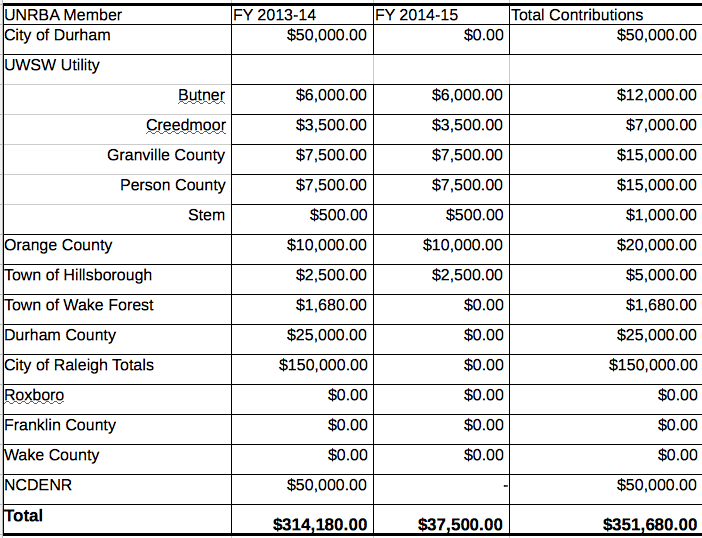

The City of Raleigh has set aside $150,000 in Falls Lake research to make up for a lack of state funding.

The research is expected to increase the options and reduce the cost to comply with the pollution reduction requirements of the Falls Lake rules.

Other governments with jurisdiction in the Falls Lake watershed have verbally committed to match Raleigh’s funds with another $150,000, including $50,000 from Durham.

While Wake County has been involved in the process, it hasn’t dedicated any funding.

The state Department of Environment and Natural Resources’s (DENR) plan for pollution reduction from developed land was rejected by the Environmental Management Commission in July, sparking the need for more research before a new plan is presented in 2015.

“Ideally the people of the state would pay for all of this as opposed to just the people in the Falls Lake watershed,” said Rich Gannon, nonpoint supervisor with DENR’s Division of Water Resources. “However, the practical reality of it is that there is no stream of funds appropriated for this work.”

Raleigh Deputy City Attorney Dan McLawhorn said the Division of Water Resources is funded through the state budget or grants from the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

“DENR wasn’t getting money from either place with which to do the work,” he said.

DENR did receive a grant of $50,000 for the project to bring funding to $350,000.

The Upper Neuse River Basin Association, whose members include city and county government representatives and other stakeholders, is coordinating the effort.

Raleigh’s funds come from the watershed protection fee, a penny per 100 gallons surcharge on water and sewer bills that each household pays. Those funds had only been used in the past for land protection.

The Existing Development Rule

Land’s capacity to absorb rainfall is reduced when cleared and covered with pavement, buildings and other infrastructure.

Rainwater that is not absorbed flows downhill, picking up nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, among other things. Those nutrients, phosphorus and nitrogen, often end up being swept downstream to a lake, where they cause algae blooms and increased water treatment costs.

This process leads to nutrient pollution, which the Falls Lake Rules were developed to address. The rules, which became law in 2011, provide a plan to reduce pollution in the lake during the next 30 years.

The portion of the rules that addresses existing development requires local governments to tally the nutrient pollution from all construction that occurred between 2006 and 2012 and offset it by 2021.

The local governments submitted inventories in January that begin to tally the nutrient sources.

For example, if a developer constructed a home that has runoff from the roof that contributes 2 pounds of nitrogen and 2 pounds of phosphorus per year, the city or county in which that house was built must now pay to capture and treat those nutrients.

Various strategies are used, but nearly all involve slowing or capturing runoff water that would otherwise carry those nutrients to the lake.

The wetland at Fred Fletcher Park in Raleigh is a BMP.

The science behind treating runoff to prevent nutrient pollution is relatively new and continues to develop.

McLawhorn said, “This is cutting edge nationally. EPA doesn’t have a handbook that tells us the value” of nutrient reductions for each of these practices.

Governments, developers, and others who need to develop land in the watershed can only gain credit for practices approved by DENR.

And because every watershed is unique to some degree, each practice has to be evaluated for its applicability to the Falls Lake watershed.

The existing development rule requires that DENR defines allowable practices for the local governments in a model program. The governments will then use the model as an example for their actual program.

DENR’s First Attempt

DENR presented a model program to the Environmental Management Commission (EMC) in July, but the EMC rejected the program at the request of governments in the Falls Lake watershed, including Raleigh and the DENR

representatives.

John Huisman, Neuse River and Falls Lake Nutrient Strategy Coordinator with DENR, said governments in the Falls Lake watershed, including Raleigh, “wanted additional [practices] identified with the most cost-effective methods and to establish nutrient credits for other [practices].”

The EMC gave the stakeholders time to work on that.

“We agree that this will make the process better and improve the quality of the program,” said Forrest Westall, executive director of the Upper Neuse River Basin Association.

Cardno ENTRIX and the Center for Watershed Protection, environmental consultants, have been chosen to complete the project. Westall wrote in an email that the project will evaluate 20 to 25 out of 60 practices that the river basin association identified.

The Falls Lake Rules only requires the state to provide a model program—it doesn’t say who is supposed to pay if the model program is found to be inadequate.

“The feeling of pretty much all of the local governments that I have been in contact with in the Falls watershed and the Jordan Lake watershed is that yes, the state should be paying for this,” said Michelle Woolfolk, water resources engineer for Durham. “We shouldn’t be paying for this.”

According to Gannon from DENR, “it is not for lack of interest in funding this effort.”

He said that EPA has given DENR a tentative commitment of $35,000 of a federal contractor’s time to study three practices that could not be included in the Cardno ENTRIX study.

After the research is complete, DENR officials will review the findings and recommend which practices to allow credit for in the Falls Lake watershed.

DENR and the river basin association stakeholders have until July of 2015, their next date with the EMC, to develop a new model program.

Six months after that, the local governments will have to present their programs to DENR for approval. The existing development deadline is unchanged, requiring all nutrient pollution from 2006 to 2012 to be offset by 2021, when stage one of the rules ends.

Durham has already taken action to offset nutrient pollution and is keeping track.

“There are some things that are proving to be more efficient, more cost effective than the things that are currently approved by the state,” Woolfolk said. “But we may not be allowed to get credit for them, which means that we won’t use them even if they are more cost effective.”