Brought to you by Rufty-Peedin Design Build

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

Ordinarily when there’s no subject matter for our regularly scheduled Teardown Tuesday column, we swap it out with something like Terrific Tuesday.

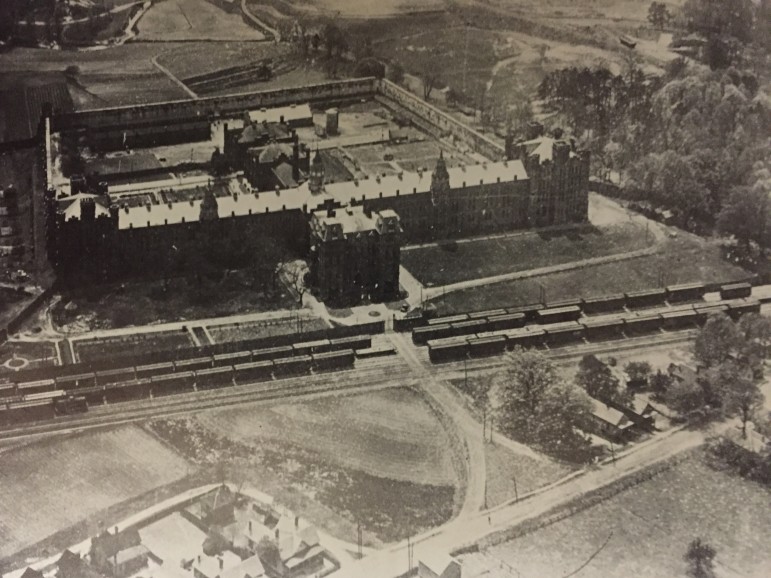

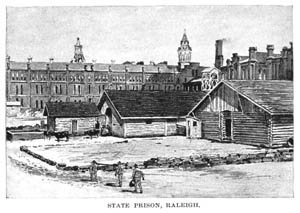

It’s usually a look at an older building in Raleigh; earlier this month we covered NC State’s Carmichael Gymnasium. Today’s subject is the old Central Prison, so calling it Terrific didn’t seem appropriate.

State of North Carolina

The old State Penitentiary

As always when writing about historical buildings, we check to see whether it’s already been covered by Goodnight Raleigh. There was a brief Flashback Friday post about a 1907 postcard that contained a pretty striking photo of the old prison; it’s definitely worth checking out.

90 years before that postcard was sent to a sailor aboard the USS Galveston, reform efforts were underway in the state legislature to improve the quality of the state’s judicial system.

Although Elizabeth Culberston Waugh said reported that discussions about a state penitentiary — at the time, criminals were dealt with on a county level — began in 1815, the earliest mention we could find was 1817, as described in an academic paper on antebellum North Carolina.

The biggest victory for the reformers in 1817? Making horse-theft a “clergyable” offense.

Apparently, the concept of a clergyable offense is tied into old English law. I found a definition that read: “Entitled to, or admitting, the benefit of clergy.” Oh.

To make a convoluted concept short: if you committed a clergyable offense, you get to live. If you committed a non-clergyable offense, well, so long friend. Until 1817, stealing a horse got you sent to the gallows in North Carolina. An unrelated but morbidly interesting fact; in that same academic paper there was a description of an 1830 public hanging of prisoners where it noted the majority of the crowd was made up of women. Not what you’d expect.

As long as we’re on the subject of tangentially related material I came across while researching today’s piece: there were 18 German Prisoner of War Camps in North Carolina during World War II. None were in Raleigh.

Three hundred words in and we haven’t even gotten to the prison, so I’ll cut it out with the miscellaneous facts for now.

Three hundred words in and we haven’t even gotten to the prison, so I’ll cut it out with the miscellaneous facts for now.

In 1868, the North Carolina State Legislature established a new, Reconstruction-era Constitution that allowed for the construction of an official state penitentiary.

A little more than 40 years earlier in 1846 however, there was, according to Jason Tomberlin, “a statewide vote on the desirability of a state penitentiary, but North Carolina’s voters, many of whom still believed in the efficacy of corporal punishment, such as whippings, croppings, and brandings, overwhelmingly disapproved of the plan.”

Essentially, the concept of centralized state prison didn’t fulfill the citizens’ bloodlust.

Two years after the new Constitution was established, the first phase of the inmate-built prison was completed. According to Tomberlin the penitentiary’s assistant architect described the structure thusly:

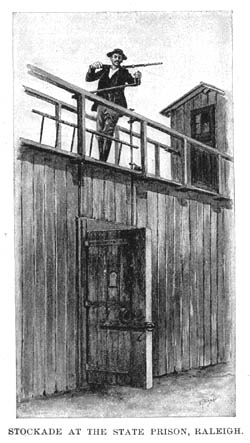

“The Work has been as follows: 2965 ft. Prison Stockade made of long leaf pine poles, hewed on two sides placed close together and set four (4) in the ground, standing fifteen (15) ft. above ground. In which are two (2) large Wagon gates, one (1) Railroad gate, and one small gate for entrance of Persons on foot.”

State of North Carolina

The original wooden stockades

Waugh, for her part, described them as “log-cabin detention blocks.”

The first prisoner housed in one of these blocks was Charles Lewis, 22, who had been arrested for robbery in Johnston County. The next two prisoners were, perhaps not surprisingly, his accomplices. They weren’t able to break out of a wooden prison, so it’s unlikely they were master criminals.

The actual brick-and-granite penitentiary was designed by architect Levi Tucker Schofield. If there’s a vague association between prisons and the name Schofield, it’s likely you’re a huge fan of state history, or you were a fan of the Fox series “Prison Break.” The show’s main character was an architect named Michael Scofield, who got himself arrested so he could break his brother out of prison. I’m pretty sure he would have made quick work of those log-cabins.

The real-life Schofield, who was based out of Ohio, designed in his home state the Asylum for the Insane in Columbus and the Late-Victorian style Athens Lunatic Asylum in Athens.

The state penitentiary in Raleigh, which was built on the site of what is now Central Prison on Western Boulevard, was designed in the style of a “Medieval, Gothic bastion.”

Work on the 500-cell prison was not completed until 1884, at a total cost of $1.25 million. The first block of 64 cells, however, opened in 1875.

Throughout the years, the facility received a number of upgrades, including a shop and main building designed by Bernard Crocker.

Unfortunately, by 1954 all of the original “turrets, battlements, spires and pointed cupolas” were condemned by the building inspector and “removed, one by one, until none remained.”

Waugh is often dramatic in her descriptions.

The prison was eventually demolished in 1983, about 33 years too early for a Teardown Tuesday column. Too bad.