Most people don’t give their drinking water too much thought. As long as it’s clean when it comes out of the faucet, all is well, right?

Anyone familiar with my previous work with the Record knows I’m a water geek. It wasn’t always this way. Growing up on Long Island I was surrounded by the stuff. I loved the beach and did a seven-year stint as a pool lifeguard.

But, it wasn’t until I started writing for the Record that I really became interested in how water went from running off our driveways to flowing out of our faucet.

In the past four years, I learned a lot about Raleigh’s current water infrastructure system, but didn’t know too much about its history.

Today, our primary uses for water include drinking and cleaning, but it wasn’t always like that.

In the days before electric light bulbs, fire codes and flame retardant furniture, an entire city going up in flames was a very real risk.

“People bringing water to American cities were much more concerned with fighting fires than washing or drinking,” Raleigh-based author Scott Huler says as he narrates the first video in a series about Raleigh’s water infrastructure.

Raleigh’s first go at creating water infrastructure was in the early 1800s when only about 1,000 residents call the city home. In 1818 the city built a water wheel in the Rocky Branch creek, which pumped water through wooden pipes to a water tower.

“Think barrels,” wrote Huler in a follow-up email. “Staves held together by wire, wound around almost like a spring.”

Unfortunately, Raleigh’s first try at a citywide system was, to put it bluntly, a total disaster. The mud and silt that accompanied the water caused the pipes to burst and within a few years the city returned to wells and pumps.

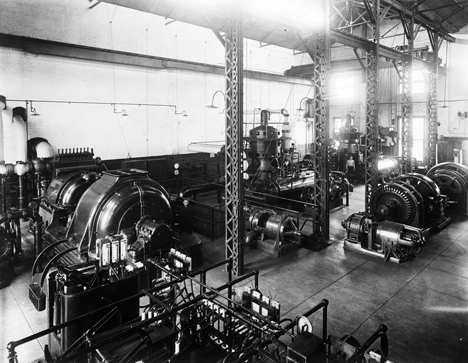

North Carolina State Archives

A 1925 photo of a Ralegh Steam Plant

In the mid 1880s, with the population at a booming 10,000 people, Raleigh decided to give it another try. In 1886 the city built a real pump, just south of downtown, pulling water from Walnut Creek. The steam-powered water treatment plant filtered 2 million gallons per day sending the water to a reservoir and then to a 100,000-gallon water tower that still stands downtown.

By 1910 Raleigh had 55 miles of water mains running beneath the streets.

The system continued to grow and by 1923 the city opened two connecting reservoirs, Lake Raleigh and Lake Johnson, which were both in the Walnut Creek watershed.

Less than five years later, the city diversified its supply and began pumping water from the Swift Creek watershed.

Much like today, Raleigh’s growth quickly began to outpace the city’s infrastructure. By the late 1930s the old plant had reached its capacity at 7 million gallons per day.

Using federal funds from New Deal programs and city bonds, Raleigh constructed the E.B. Bain Water Plant to serve its 50,000 residents.

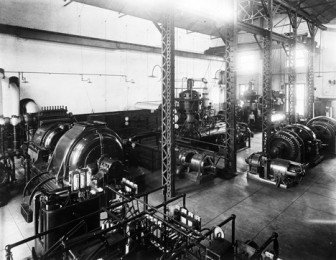

North Carolina State Archives

A photo of the EB Blain Plant

While it may sound cold and mechanical, the plant was anything but. “It said something different about a water treatment plant,” says retired water plan supervisor John Garland in Huler’s video. Garland said the plant’s ornate design was meant to impress those that walked through the door, signaling the city’s dedication to clean water.

The plant processed 18 million gallons per day, eventually topping out at 20 million gallons. In the 1950s two more reservoirs were built on Swift Creek holding 3 billion gallons of retained water.

When the population finally hit 100,000, residents the city had to start looking for other water sources that would provide the flow required to keep the faucets running. In 1967 the city built the E.M. Johnson Water Treatment Plant on the Neuse River just as the city began to see a wave of rapid growth.

About 100 years after the first pumps began pulling water from Walnut Creek, the city and the Army Corps of Engineers opened Falls Lake, capable of holding 43 billion gallons of water, only a portion of which is used for drinking.

The system has since expanded to include Lake Benson in Garner and the city provides water to several municipalities within Wake County.

“Raleigh didn’t have to work hard to keep up with growth when it was growing slowly,” wrote Huler. “Since the 60s it’s done a fairly good job in keeping up regarding both water and wastewater.”

As Raleigh, and the towns it serves, continue to grow, public utilities officials find themselves once again in a race to increase supply.

Raleigh officials have tapped the Little River as its next potential reservoir, but must first exhaust all other options that have less of an environmental impact. Even with the Little River, the city is still in sort supply.

There have been talks in recent years about pumping treated wastewater back into Falls Lake where it would re-enter the system. Despite the lake already containing treated waste water from Durham and other municipalities north of Raleigh, there is an ick factor associated with the practice. It would also need state approval.

In October, much to the delight of this Johnson County water customer, the city and the county signed an interlocal agreement that would coordinate water planning efforts in the Neuse River basin.

Although the city has a long way to go in planning for the future, the city has come quite a ways since wooden pipes carried water to Raleigh’s earliest residents.

North Carolina State Archives

A photo of an early water reservoir