At 444 pages, the North Carolina Oil and Gas Study is an extensive document. During the month of April, Laura White will be tackling this entire document, conducting interviews with experts and breaking it down section by section so you can be as informed as possible.

The Record’s goal here is not to tell you what to think about fracking, but to arm you with the information you need to make an informed decision.

Check in a few times a week, and watch for #NCFrackFocus on Twitter for daily updates as we work our way through what you need to know. Have a specific question you want us to address? Email lwhite@raleighpublicrecord.org or Tweet @lewhite.

This section begins, like any good work of literature, by establishing a setting.

According to the study, North Carolina has been known to produce coal as early as the Revolutionary War period, and Subgroup A of this section reads largely like a natural history of North Carolina’s geography while chronicling the past exploration of those fuel resources.

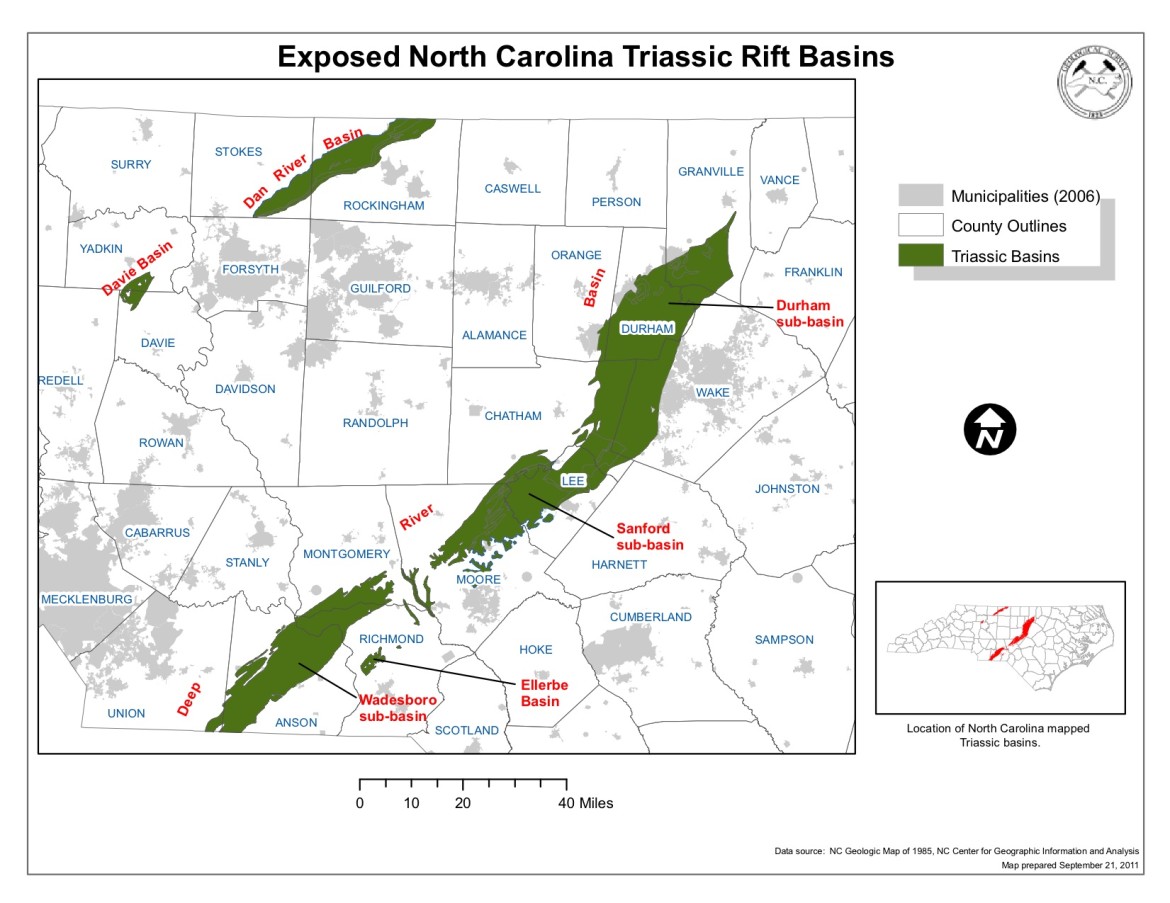

North Carolina's Exposed Triassic Rift Basin. Image courtesy DENR.

Fun fact: we’ve apparently been drilling for gas since 1974, but didn’t hit the spot until the last two wells were drilled in 1998 — though none of that gas was recoverable.

The second subgroup of this particular section deals with organic geochemical data, citing 2008 as the first time the North Carolina Geological Survey recognized the shale bed in the Deep River Basin as a potential gas resource. In 2009 the NCGS sampled the last two wells drilled in NC — Butler #3 and Simpson #1 — and began to evaluate the gas for potential commercial production.

If you’re interested in learning more about this process, and how these two wells helped determine the potential target location of the Sanford sub-basin — more than 59,000 acres of land — you’ll want to read this subgroup, starting at page 19 of the report. It goes into a bit of necessary depth describing a lot of the technicalities of determining the available resource, and what those technicalities mean. I could try to re-explain them here, but the report does a nice job of breaking it down, and I’m not sure I could do it in any less words than the draft does.

There’s also a helpful map showing exactly where this 59,000 acres is located, and includes seismic lines as well as prior coal, oil and gas exploration sites.

Image and text from the DENR study. Click for a larger version.

Subgroup C of this section addresses the issue of estimating how much gas can be recovered from the Deep River Basin — a crucial aspect of understanding the impact drilling will have economically, socially and environmentally.

The last official USGS oil and gas assessment was published in 1995. While the USGS is working on a study currently, it’s not set to be released until this summer, so the results couldn’t be included in this draft, given the time constraints.

Because of that, DENR had to use the limited data available — information from the two wells drilled in 1998 — to develop their estimates. This means these estimates are only applicable to the Sanford sub-basin, which is just one part of the entire Deep River Basin, and can’t be applied to all Triassic Basins in North Carolina.

DENR stresses in the report that even for this sub-basin, two wells is a very small sample size. The data collected from the two wells is also significantly different, so it’s unclear how representative these averages can be, and DENR states that it is likely the estimate will change once more information becomes available.

Whoa. Wait. What? This reads like a big, burning red flag to me. In the very first section of this very massive report, the people making some very significant calls for NC on the nature of this resource that has to be extracted by controversial means tell you they just aren’t sure? I couldn’t help but think of what I’ve heard so far from experts at committee meetings and town hall sessions: What’s the rush? Wait until we are sure.

Apparently, that gas has been there for a while, and isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Even DENR goes on to suggest forming a collaboration between the government, academia, and industry to drill test wells — all vertical and without hydraulic fracturing — in order to obtain more accurate estimates. Considering that one of the wells in NC’s past — Elizabeth Gregson #1 — completely missed the shale formation when it was drilled in 1987 because seismic data collected in the prior two years had not yet been fully processed, it seems the more accurate the estimates the less likely we are to do waste money/time/resources. What is it they say, learn from history or you’ll repeat it?

Subgroup D of this section addresses the anticipated industry behavior in regard to the potential resources (this is what we think will happen based on information we aren’t sure of), beginning with an outline of the history and protocol of drilling in NC. There are already four companies that have signed leases in Lee County: Whitmar Exploration Company, Hanover NC LLC, NC Oil and Gas LLC and Tar Heel Natural Gas LLC.

Meaning these four companies already have land. Quite a bit of land.

These companies combined have 79 agreements totaling 9,297 acres of land. Given regulations regarding distance between wells, and assuming that 160 acres is necessary for one well and that not all of these acres are contiguous, a total of 33 wells could be sited on land already under lease. The report estimated that as many as 368 wells could be potentially drilled in the Sanford sub-basin alone if we make a decision to pursue fracking commercially.

The report does make a point of mentioning, though, that because there are already a lot of producing fields, drilling rigs are busy and a natural gas company is not likely to move a drill rig from a producing field to one with an unknown resource value.

That sounds like more uncertainty for an issue people are passionate about in no uncertain terms.